In 2017 the ‘decline narrative’ had become widely accepted by Western researchers focused on the Jihadist movement. In contrast, in November 2017 we predicted that ISIS media would continue to fluctuate in 2018. This was based on an archive of digital and digitized content. The digital Jihadist content which stretches across more than two decades, 300,000 pages of Arabic text, 6,000 videos, hundreds of hours of audio (including 600 hours of ISIS radio programs). The archive of digitized content stretches even further back, given the nature of content of the 1980s, for example, that was later digitalized and is part of what the Sunni extremist movement shares.

During 2017 much was being written about the ‘sharp decline’ of ISIS media and even demise of a physical Caliphate. Our prediction faced opposition from those who were pushing the ‘post-Caliphate’ decline ‘narrative’ and particularly those who seemed to be staking their reputation on the continued decline correlated to territorial loss.

In January 2018 Jade Parker and Charlie Winter announced “a full-fledged collapse” of ISIS media.[i] Only days later, it became clear January 2018 had also witnessed a 48% month-on-month increase in ISIS content production.[ii] In addition, rather than a full-fledged collapse, in March 2018 ISIS were still able to drive traffic to their content, with some videos getting over 12,000 views on Twitter.

As we have said before, just because non-Arabic and faux-Arabic speaking researchers cannot find it, does not mean the content does not exist – nor does it mean the target population for the content cannot find it.

It is clear today that rather than moving from media decline to “full-fledged collapse”, ISIS media continued to fluctuate as we predicted. This more complex representation relies on differentiating decline and degradation from a period of reconfiguration – as we have been saying since 2014.

This post shows that the Jihadist movement is much more complex than those pushing the ‘decline narrative’ suggest. It shows why counting the number of videos has little bearing on the amount being communicated – which after all is the purpose of producing the videos.

Recognising the limits of the contemporary ‘metrification’ approaches, along with the cherry-picking of timepoints and the overemphasis of pictures on which the decline narrative relies, we focused on in-depth analysis of strategy, Arabic documents, audio and video to produce an authentic representation of the movement.

So, how did we know?

Based on a genuine collaboration between subject matter expertise and data analysis, we uncovered the answer as a combination of two factors;

- The jihadist movement operates on a much longer timeline than appreciated by pundits looking to produce tweet-ready metrics.

- While many western commentators were pushing the ‘decline’ narrative, based on the over-representation of pictures, video production which had been low over the summer had already begun to increase again during the autumn.

These elements and in-depth analysis of the movement allowed us to make the prediction before the event, in contrast to the many ad-hoc descriptive responses after the event.

How did we do it?

After building an archive of over 300,000 pages of Arabic text, and 6,000 videos, and hundreds of hours of audio produced since the 1990s, it was clear that long form matters to the core of the Jihadist movement. And this does not even touch on the wealth of magazines created in the 1980s by Sunni extremist groups.

In the thousands of pages of Arabic text, strategy was clearly articulated for those able to read Arabic and willing to invest the time to understand the references, context and encoded meaning. Getting past what Nico Prucha refers to as the “Initiation firewall”, means you need to have read and consumed the content in Arabic to understand the depth of theology which is used as coded communication. Yet, in most research not even transliterated Arabic keywords that matter for the Sunni extremist movement and are used as codes in English-language publications matter and are properly analysed.

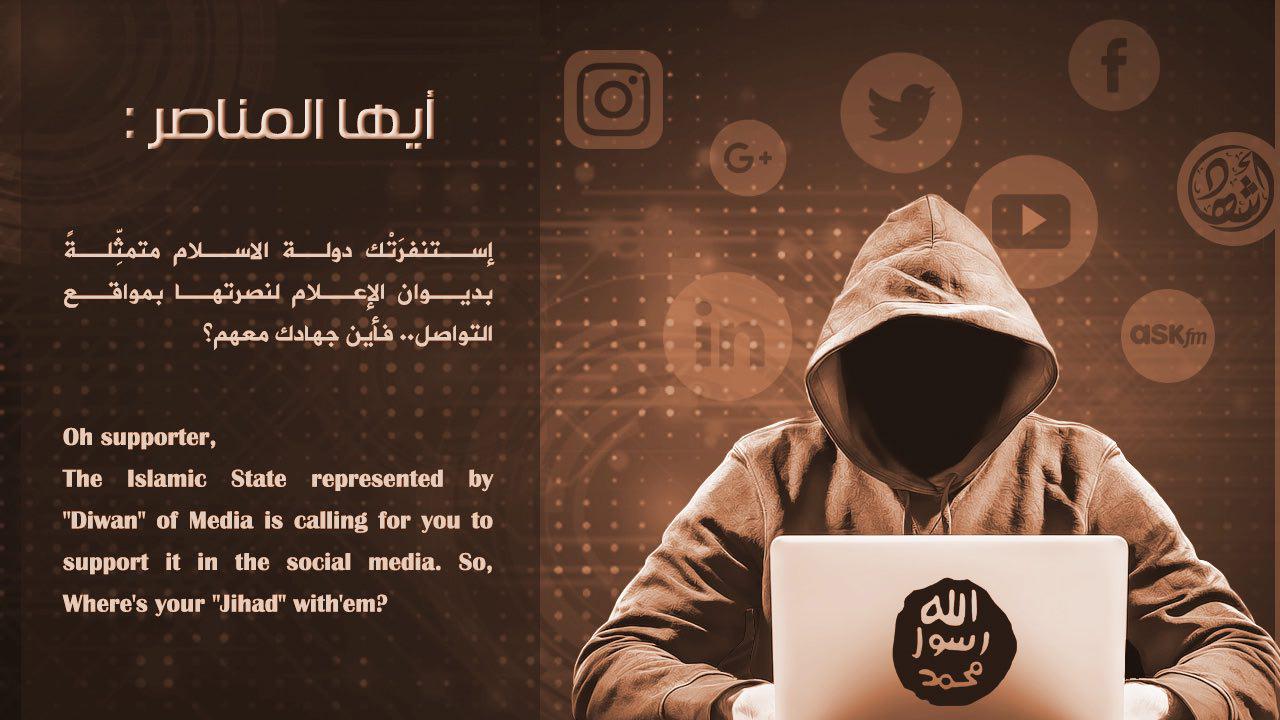

Content, especially Arabic language content, is fundamental to the movement, yet the lingual & theological expertise to understand it is almost constantly neglected and lacking in research. This blind spot allows the jihadist movement to reorganize and recuperate out of view of contemporary research and commentary. This allows the movement to develop strategy and tactics by leveraging a wealth of material shared online – and re-organize and develop new outreach strategy. These online spaces provide a safe-haven of coherent theological framework and invites individuals – based on their individual degree of initiation – into more and more clandestine networks, involving layers of online vetting processes.

These clandestine networks are protected by:

- Arabic language required to access clandestine networks, the ongoing paucity of these language skills amongst researchers is appalling (lingual firewall),

- Knowledge of the coherent use of coded religious language and keywords, which few researchers can demonstrate in their writing (initiation firewall),

- With the migration to Telegram, ISIS succeeded in shifting and re-adapting their modus operandi of in-group discussions & designated curated content intended for the public (as part of da’wa).

Passing these firewalls provided access to what ISIS – and the Jihadist movement more broadly – are trying to achieve. [Spoiler alert] What they seek has nothing to do with ‘Utopia’.

Unfortunately, a rigorous understanding of Arabic and deep appreciation for the theological references that Jihadists use simply do not seem to matter to commentators who have become pre-occupied with the few English items and pictures that they have found (though even these are not necessarily understood).

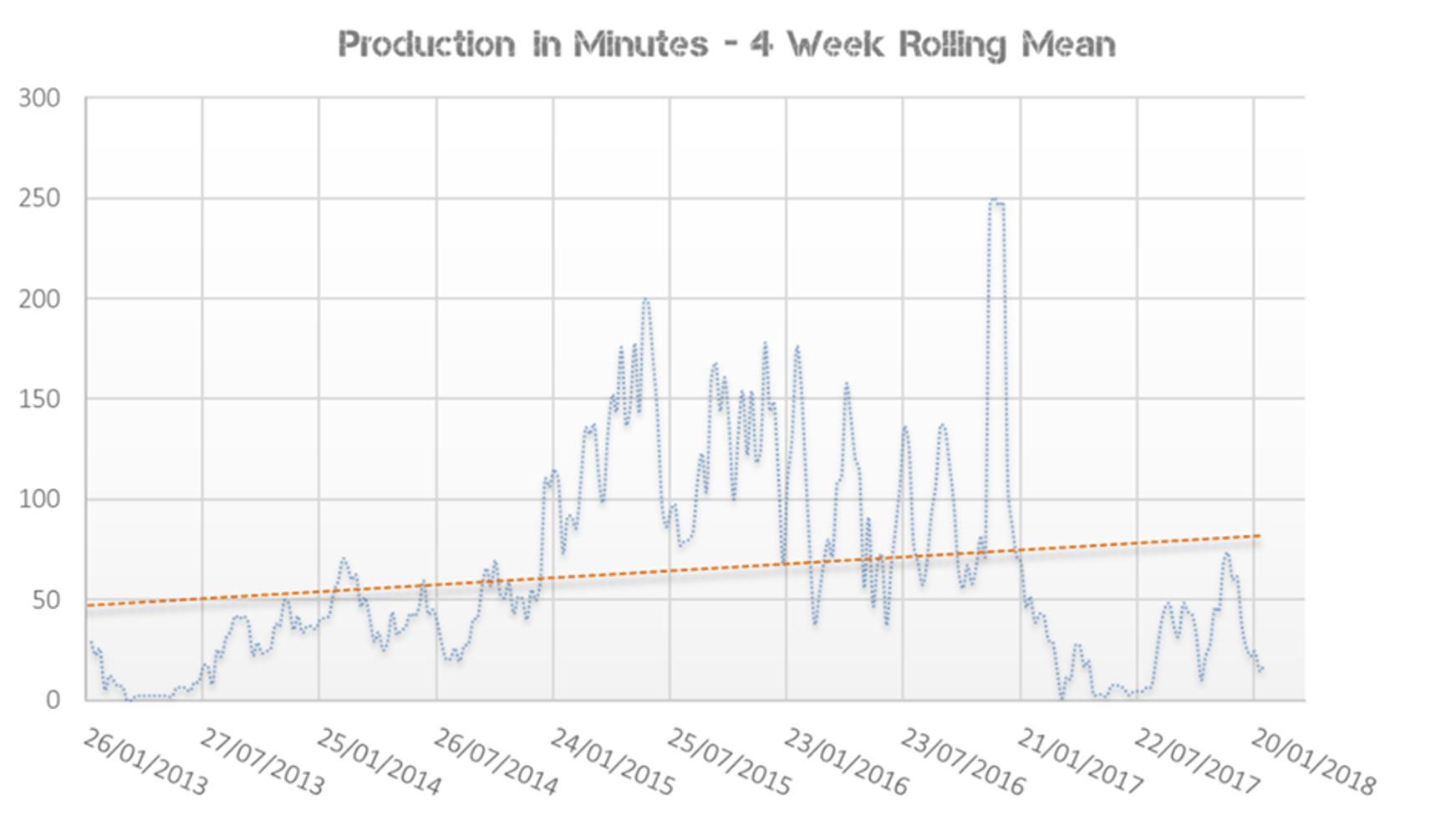

Using the strategic approach adopted by ISIS, and the Jihadist movement, as a point of departure, we examined the amount of video being produced since ISI transitioned to ISIS.

Using the longer timeline and rolling mean of the number of videos produced, it is easy to see that the most likely outcome would be that ISIS media would continue to fluctuate rather than follow the linear ‘direction’ of decline.

Two points provide an important book-ends that further disrupt the decline narrative. First, the highest peak falls before the much talked-up ‘high-point’ in content production. Second, the next highest period of video production fell at the end of 2016 and is much higher than the rest of 2016, exceeding almost the entire history of ISIS video production. This repeats the finding of earlier research which also highlighted the fluctuation in content.

Just as magazine production going back to the 1980s and 1990s fluctuated, so all forms of media production fluctuates.

Equally, as the end of 2017 approached and many western commentators were pushing the ‘decline’ narrative, video production which had been low over the summer had already begun to increase again.

These findings are in sharp contrast to the massive overemphasis on pictures and tweet-ready metrics, by western researchers.

[Another spoiler alert] those who are able and inclined to read the Arabic magazines of the 1980s and 1990s will recognise all the theological themes, articles on mujahidat, defining wilaya etc. currently being passed off as new or unprecedented by Western commentary about ISIS.

Not all content is created equal.

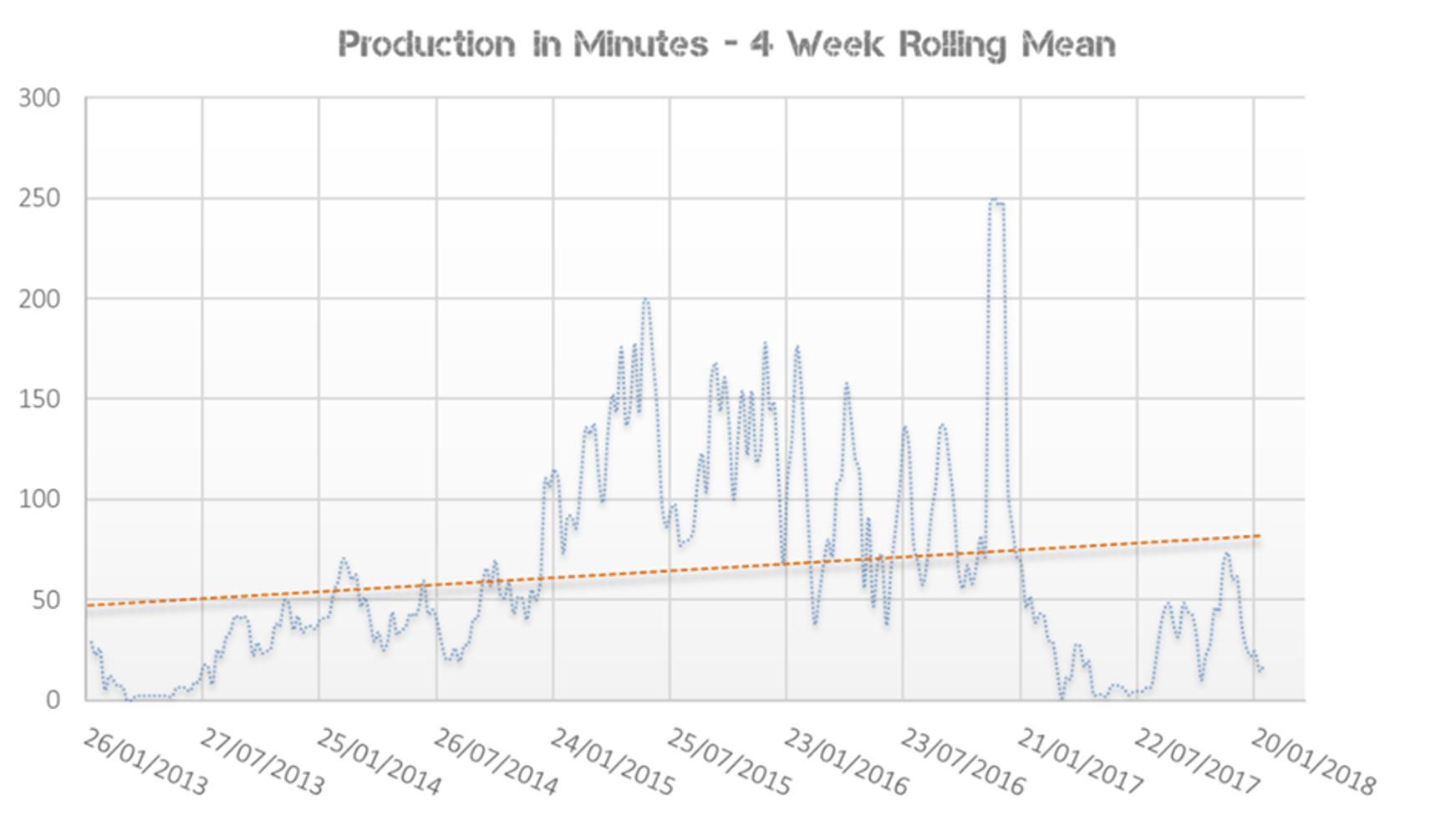

We have written before about the methodological flaw that results from counting pictures, video, newspaper all equally in the attempt to produce a linear metric. To examine the differences in content we looked at the length of videos measured in minutes.

Three hugely important points emerge. First, the direction of the trendline, second that measured in minutes video production peaked at the end of 2016, and third, the volume of video during late 2017 and early 2018 was higher than it had been earlier in the year.

If you take a view of ISIS from 2013 to present the trend in production is up, not sharp decline.

While picture-centric counting was hailed as showing ‘total collapse’ – the longer, more complex, and arguably much more resource intensive / important videos, were not following that pattern.

Video production in minutes during the second half of 2017 was not in decline but had been increasing. This allowed us to predict that overall production would continue to fluctuate in the face of howls of protest and decliners insisting we were ‘wrong on direction’.

Five months into 2018, the band of committed decliners has thinned significantly. Some are now even trying to sweep under the carpet the earlier claims of collapse, single downward direction, linear / steady decline, or a strong correlation with territory.

Furthermore, the assumed correlation with territory is problematic as the publications from the pre-ISIS era highlights. AQ derived great value from curated videos and writings that spanned from Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen etc. where little to no territory was held at the time.

Authenticity

We covered before why basing analysis on a cherry picked high point produces a nice narrative, but not an authentic result.

Contrasting the number of videos produced with the average length of production we find further startling results. The high point of video production comes at one of the lowest points for average length. This means that the high point was produced because ISIS published a higher number of shorter videos. While at other points, such as now, they produced fewer longer videos.

This highlights that counting the number of videos has little bearing on the amount being communicated – which after all is the purpose of producing the videos. Here we see one of the flaws in drawing conclusions from counting the amount of content produced. Producing one long video does not communicate half as much as two short videos so cannot support conclusions of ‘decline’ and collapse. Equally worth noting, the linear trend lines both show a rising trend rather than a decline in number and average length over the entire period.[iii]

Metrification:

Tweet-ready punditry has led commentary to focus on finding and tracking a magic metric rather than developing an authentic understanding of the movement (a trend policy has, to an extent, followed). However, there can be no doubt now that magic metrics pushing decline and full-fledged collapse have failed to provide an authentic representation of the movement.

These metrics have been used to justify pronouncements of decline and ‘total collapse’ in ISIS media and claims production is strongly correlated with territory – which, while headline grabbing, have failed to hold up to scrutiny in 2018, just as the passage of time has shown previous claims of decline and degradation to be more wishful thinking than evidence based conclusions.

Three elements, previously highlighted by Richard Jackson, are particularly prescient when reflecting on the recent metrification of research into the Jihadist movement.

Specifically, the tendency toward:

- treating the current problem as unprecedented and exceptional

- descriptive over-generalisation,

- problem solving approaches that risk reducing research to ‘an uncritical mouthpiece of state interests’

Unprecedented and exceptional

Richard Jackson observed that there has been a “persistent tendency to treat the current terrorist threat as unprecedented and exceptional”.[iv] Representing the current threat as unprecedented and exceptional in nature, is a helpful tool if one were to want to start analysis at a preferred point – rather than account for what came before – or account for any relationship between previous iterations of the movement and the contemporary situation. This is important not least because ISIS draw extensively on content and experiences from previous iterations of the movement.

There have been a rash of studies over recent years focusing on ‘official’ social media accounts or what is often termed ISIS ‘official’ media. They use data which starts in 2014 (or strangely 2015) and occasionally – the totally bizarre approach of drawing conclusions using only a single time point before 2017. This approach enables a simple metrification – but undermines authenticity by separating the analysis of the movement from its historical roots. The cherry picking of time points allows everything to be boiled down to a magic number without reference to what came before thereby providing a policy friendly ‘narrative’.

However, the Media Mujahidin did not appear one day out of nowhere. It evolved over two decades of online activity – tied into the jihadist tradition of producing media since the 1980s during the jihad against the Red Army in Afghanistan.

A previous post demonstrated that once we get away from the narrow discussion of ‘core’ nashir channels we can escape the over-generalisation based on a tiny sample of channels. Taking a wider perspective shows that rather than being a few disconnected channels, the network structure allows Jihadist groups to maintain their resilience and distribute the full range of content. Jihadists groups have been observed using these structures since 2013, and building on these observations, it is clear that this current iteration, like the movement in general, is neither unprecedented nor exceptional.

Descriptive over-generalisation

Reviewing the articles published since 9/11, Richard Jackson observed “the vast majority of this literature can be criticised for its orientalist outlook, its political biases and its descriptive over-generalisations, misconceptions and lack of empirically grounded knowledge”.[v]

Over the years, metrification and over-generalisation have resulted in numerous claims of degradation and decline, culminating in recent pronouncements of ‘total collapse’. In time, all these claims have been shown to be misplaced. This is because, as noted in 2014, “the nature of the mobile-enabled swarmcast means it can appear to be degraded, but it has really only reconfigured”.

The level of over-generalisation from a few limited observations and ongoing metrification have been key parts of the decline ‘narrative’. Unfortunately, it risks peering down a soda straw at a large-scale complex problem , to borrow an analogy from Kill Chain. For example, the VOX-Pol study Disrupting Daesh concluded “IS’s ability to facilitate and maintain strong and influential communities on Twitter was found to be significantly diminished” and that “pro-IS accounts are being significantly disrupted and this has effectively eliminated IS’s once vibrant Twitter community”.[vi]

These findings are an overgeneralisation, just like previous claims, based on extrapolating from the soda straw perspective of researcher’s inability to find twitter accounts. The evidence from beyond the soda straw shows ISIS continued to drive traffic to their content. Twitter represented 40% of known referrals to ISIS content during the time period of the VOX-Pol study.[vii] If ISIS had been significantly disrupted – where was the traffic coming from?

This type of over-generalisation has been key to the decline narrative. In another example, Peter Neuman claimed:

Instead of populating mainstream social media platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, Islamic State supporters have been pushed into the darker corners of the internet, especially the private messaging app Telegram, where reaching out to new supporters is more difficult.

Directly contradicting that claim, in addition to the 12,000 views on a video in March, shown earlier, a sample from consecutive days in May 2018 shows ISIS videos still being watched thousands of times on Twitter – 7,351 views, 9,192 views and 8,699 views on 12th, 13th and 14th May respectively. A clear indication that outreach is ongoing via Ghazwa, as core members access content via Telegram. The success of this uninterrupted outreach process adds to the coherency that ISIS texts and videos offer to their target audiences.

Risks of being an uncritical mouthpiece

A third observation central to the development of Critical Terrorism Studies equally highlights the limitation of an approach based on problem-solving metrification;

“It is fair to say that the vast majority of terrorism research attempts to provide policy-makers with useful advice for controlling and eradicating terrorism as a threat to Western interests”. This problem-solving approach can “be a real problem when it distorts research priorities, co-opts the field and turns scholars into ‘an uncritical mouthpiece of state interests’”.[viii]

The narrative of ISIS in decline, in addition to undermining what they claim as a “utopian picture of life under Daesh rule”, or what Rex Tillerson referred to as the “false utopian vision”, have been parts of the strategy adopted by the Global Coalition against Daesh.

That the decline ‘narrative’ has been pushed so hard by some commentators insisting on their being a ‘direction’ – there has been a growing risk of some becoming uncritical mouthpieces.[ix] For example, the idea of ISIS seeking to project a utopian vision is uncritically accepted by many Western commentators. This subsequently distorts the interpretation of ISIS media. For Jihadist groups Utopia is not a concept to which they aspire. This is due to the theology which draws a clear distinction between the worldly concerns or the temporal world (dunya) and paradise (janna). Even so, academic references connecting ISIS to Utopia proliferate, without reference to original jihadist content that discuss ‘Utopia’ as a goal for their activity.

More troubling than the lack of critical thinking about the core concepts of the jihadist movement are the whispers of researchers working with / for Coalition members and their contractors one day, and the next day representing themselves as independent journalists writing about ISIS decline or Coalition success.

Clear disclosures of potential conflicts of interest between journalism, research, and Government interests are fundamental parts of producing credible academic findings.

If these whispers are confirmed, it would realise one of the objectives outlined by Jihadists including Abu Mus’ab as-Suri, to show Western society contradicting the values to which they claim to adhere. It would be a completely ridiculous and entirely avoidable own goal.

It would also be a breach of journalistic ethics akin to Sean Hannity’s less than full disclosure and represent one of the most profound breaches of trust in the publication of research since the CIA was found to be covertly channelling money to Encounter Magazine and the Congress for Cultural Freedom.

Conclusion

Problem-solving punditry, metrification, and the ‘decline narrative’ have become widely accepted by Western researchers focused on the Jihadist movement. However, as this post has shown the Jihadist movement is much more complex than those pushing the ‘decline narrative’ suggest.

Recognising the limits of metrification, the cherry picking of time points and decliner emphasis on pictures rather than in-depth analysis of documents and video, will allow researchers to produce a more authentic understanding of the movement than is possible from simple linear metrics.

As Rüdiger Lohlker wrote in September 2016,

“without deconstructing the theology of violence inherent in jihadi communications and practice, these religious ideas will continue to inspire others to act, long after any given organized force, such as the Islamic State, may be destroyed on the ground;”[x]

ISIS has the upper hand by inhabiting places that are blind spots for outsiders. They use these blind spots to their advantage. Rather than collapse, ISIS continue to produce coherent content in Arabic – content of which hardly seems to matter to most policy makers and researchers. They build resilient, regenerative online networks – that are now completely in the dark for outsiders. They have battle-hardened fighters on the ground, and the intellectual capital— “their weapon designs, the engineering challenges they’ve solved, their industrial processes, blueprints, and schematics” – from what Damien Spleeters calls “the industrial revolution of terrorism“.

With the commitment, knowledge and ongoing access to resilient networks, ISIS continue to publish new content (videos, articles, newspapers, radio programs etc.) from locations across MENA and ‘East Asia’.

Notes

[i] https://www.lawfareblog.com/virtual-caliphate-rebooted-islamic-states-evolving-online-strategy

[ii] Analysis: IS media show signs of recovery after sharp decline, BBC Monitoring, (23rd February 2018)

https://monitoring.bbc.co.uk/product/c1dov471#top

[iii] Worth note here, the R2 values are very low – suggesting polynomial or a longer window rolling mean might give better representations, but as we are discussing linear metrics we show it here.

[iv] Richard Jackson, The Study of Terrorism after 11 September 2001: Problems, Challenges and Future Developments, Political Studies Review, 7, 2, (171-184), (2009)

[v] Jackson, Richard. “The Study of Terrorism 10 Years after 9/11: Successes, Issues, Challenges.” Uluslararası İlişkiler 8.32 (2012): 1-16.

Jackson, R. ‘Constructing Enemies: “Islamic Terrorism” in Political and Academic Discourse’, Government and Opposition, 42, 394–426 (2007)

[vi] Conway, Maura, et al. “Disrupting Daesh: measuring takedown of online terrorist material and it’s impacts.” (2017): 1-45. http://doras.dcu.ie/21961/1/Disrupting_DAESH_FINAL_WEB_VERSION.pdf

[vii] Frampton, Martyn, Ali Fisher, and Dr Nico Prucha. “The New Netwar: Countering Extremism Online (London: Policy Exchange, 2017

[viii] Jackson, Richard, “The Study of Terrorism 10 Years After 9/11: Successes, Issues, Challenges”, Uluslararası İlişkiler, Volume 8, No 32 (Winter 2012), p. 1-16 quoting, Ranstorp, “Mapping Terrorism Studies after 9/11”, p.25

[ix] Here ‘uncritical’ refers to critical thought, rather than being negative.

[x] Rüdiger Lohlker, Why Theology Matters – The Case of ISIS, Strategic Review July –September 2016, http://sr-indonesia.com/in-the-journal/view/europe-s-misunderstanding-of-islam-and-isis