While many reports focus on social media accounts and sources that use English, Arabic is the primary language of jihadi groups globally. And this is not new. 99.9 % of all materials by jihadist groups is released in Arabic. Yet, out of a lack of lingual expertise, and an absence of “reading their lips”, has led to simple answers for Arabic illeterate audiences – produced by Arabic illerate opinion makers – out of touch with the massive ecosystem of writings. This post is about why Arabic matters, which should be evident to anyone dealing with jihadist materials due to the sheer amount of Arabic produce. To focus on this question, we repackage previously released posts, expand on the issue and emphasize, given by the evidence of collected materials, why Arabic matters.

On March 22, 2016, two bombings hit the city of Brussels. The bombings at Brussels airport and the metro station Maelbeek, which is located in the heart of the city and close by many European Union institutions, left 32 people dead from around the world – not including the three suicide bombers. As would later be the case with the Manchester bombings (May 22, 2017), several days later documents by IS were released to outline and justify these attacks. Based on theological grounds and grievances echoing from within the territory held by IS, a document was published on March 25, 2016, by al-Wafa’. The text is entitled “Ten Reasons to Clarify the Raids on the Capital [of Belgium] Brussels.” Penned by a woman by the nom de guerre of Umm Nusayba, ten reasons are clearly outlined why suicide bombers had attacked the airport and metro station. This Arabic language text has not played any meaningful role, in the media reporting or the wider academia, to understand the motivation behind this terrorist attack – in the words of the terrorists.

The same occurred when a similar text was released days after the May 2017 Manchester attack.[1] It seems that ISIS has the luxury of disseminating their coherent extremist writings well knowing it reaches their Arabic speaking target audience and bypasses the vast majority of the non-Arabic speaking counter-terrorism policy officials, academic analysts and commentators. Apart from being published on Telegram where a wider range of ISIS sympathizers are initiated into this mindset – and where most speak Arabic, the text references theological nuances and sentiments which are familiar to those acquainted with content ‘intimately tied to the socio-political context of the Arab world’,[2]

Neglecting the corpus of Arabic writings produced by Jihadist groups due to the absence of fluent Arabic speakers who understand the deep nuances of these writings is a luxury we should no longer afford. This enables content to remain online undetected in the open due to human ignorance. Caron E. Gentry and Katherine E. Brown have both shown how approaches, including cultural essentialism and neo-Orientalism, can cause a ‘subordinating silence’ which veils particular groups or perspectives from view.[3] This veil of silence still falls over the majority of the Jihadi movement which operates in Arabic, as the majority of research focuses on peripheral languages, particularly English, and interpret meaning of images based on a Western Habitus.

Violent extremist religious groups, often referred to as violent jihadist groups, have issued since the 1980s over 300,000 pages in Arabic promoting their brand of theology to justify violent jihad. In addition, contemporary Jihadist material references elements of the rich 1,400-year long tradition of Islamic writings. Part of this massive corpus are thousands of writings by the extremist Salafist spectrum. This violent jihadist theology informs their actions of violence and allows groups to communicate concepts and meaning through shared understandings of specific references, across languages, by conveying symbols and codes expressed in pictures, writings, videos or key words – strengthened by re-distributing historical and contemporary Salafist writings and, as often the case, citing these in their self-published propaganda.

ISIS shares more extremist Salafist writings (in pages) then producing their own

From ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam’s books from the 1980s Osama bin Laden’s declarations in the 1990s, or Abu Mus’ab al-Zarqawi’s statements in the 2000s (in sum 620 pages), Abu Mus’ab al-Suri’s “Global Resistance” book (1604 pages), Yusuf al-‘Uyairi’s “Constants on the Path of Jihad” (78 pages), or his “Truth of the New Crusader Wars” (119 pages), the first electronic AQ magazine “The Voice of Jihad” (in sum 1353 pages) etc.; for any Arabic speaker researching this field, “it is crystal clear – to virtually anyone who has the linguistic capacity to grasp and the opportunity to witness what jihadists are actually saying, writing and doing, both online and offline – that religion matters.”[4]

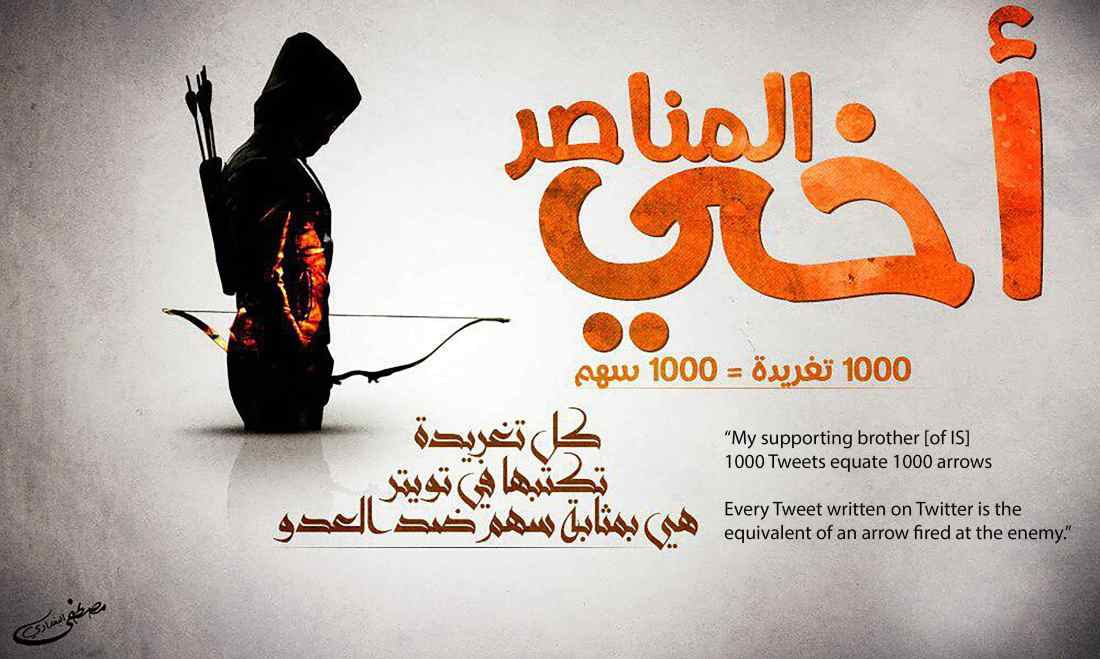

AQ, IS documents and the videos of the “Islamic State” are a treasure trove and yield to the audience the true power IS holds (and uses as nostalgia as of 2018 after great territorial loss): having (had), for the first time ever in the history of modern Jihadist movements, the power to apply theology penned by historic and contemporary theologians on conquered territory in the Arab world. This power is furthermore enhanced by the ability to project influence on the world outside of the “caliphate” by using social media as a launching pad. Sunni extremists seek to fulfil two objectives that are deemed as divine commandments: (i) commit to militancy often termed as Jihad bi-lsayf (Jihad by the sword) while (ii) being driven by the dedication to missionary work. Instead of the traditional term da’wa (proselytism), Sunni extremists, militant as well as non-militant, refer to this as Jihad bi-l lisan (verbal jihad).[5]

Sunni extremists continue operating freely online, expanding their existing databases of texts (theory) and videos (theology applied in practice) for future generations. Organizing on platforms such as Telegram allows the ‘Media Mujahidin’ to swarm on other platforms[6], social media sites and the internet in general, in their belief to fulfill the divine obligation of da’wa (proselytising) to indoctrinate future generations for their cause. Groups as IS can operate conveniently online, as their clandestine networks are protected by, as noted before:

- Arabic language required to access clandestine networks, the ongoing paucity of these language skills amongst researchers is appalling (lingual firewall),

- Knowledge of the coherent use of coded religious language and keywords, which few researchers can demonstrate in their writing (initiation firewall),

- With the migration to Telegram, IS succeeded in shifting and re-adapting their modus operandi of in-group discussions & designated curated content intended for the public (as part of wider da’wa).

Media raids ensure that dedicated content gets pumped to the surface web, ranging from Twitter to Facebook, while the IS-swarm can (re-) configure and organize content related to what is happening offline on the ground to ensure the cycle of offline events influencing / producing online materials is uninterrupted. The theological motivation, coherently repacked and put in practice, based on 300,000 pages of writings and over 2,000 videos just by IS needs to be addressed. Yet, “without deconstructing the theology of violence inherent in jihadi communications and practice, these religious ideas will continue to inspire others to act, long after any given organized force, such as the Islamic State, may be destroyed on the ground.”[7]

As outlined in this post from July 2019.

This is where we stand as of May 2020, with IS resurging for over a year in MENA and expanding in Africa, from Sahel to West Africa; not to forget the fierce battle for Marawi and the growing presence of IS in South East Asia, using both soft and hardpower. Yet, the West only seems to comprehend hardpower giving soft- and hardpowered orientated extremists areas to exploit and thrive in.

And now further details on the recent post:

The Caliphate Library on Telegram – Evidence of the importance of extremist Salafist writings

Note: for a deep diver on the Caliphate Library, please click here.

To recap:

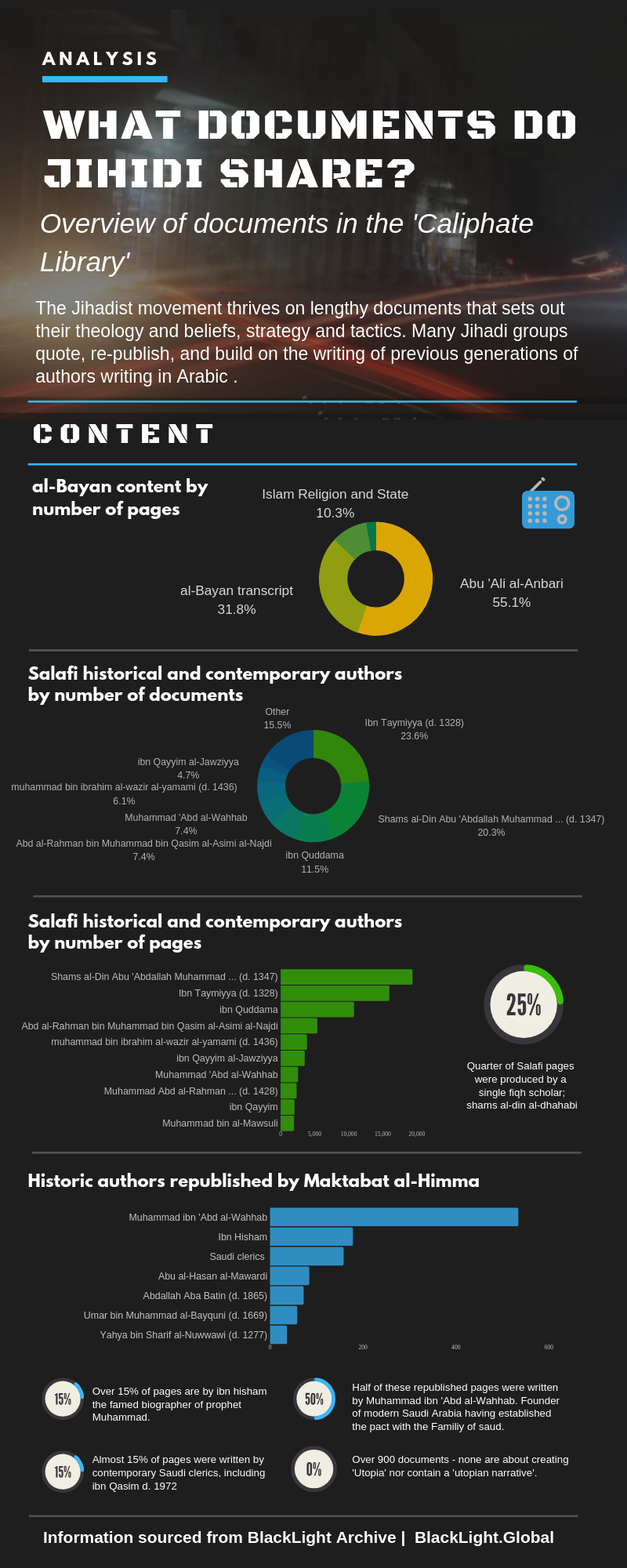

Many Telegram channels and groups operated by Jihadi groups, distribute lengthy Arabic documents. An analysis of the content shared by one such channel, ‘The Caliphate Library’ Telegram Channel shows how the Jihadi movement thrives on lengthy documents that sets out their theology, beliefs, and strategy.

Overview of findings:

- This individual library contained 908 pdf documents, which collectively contain over 111,000 pages. This is far from what one might expect from a movement which thinks in 140 characters, as some Western commentators suggest.

- In addition to the material produced by Dawlat al-Islamiyya, the channel;

- republished earlier writing through Maktabat al-Himma, a theological driven publication house of Dawlat al-Islamiyya.

- shared earlier work produced by al-Qaeda

- distributed historical and contemporary Salafi writing which intersects with their theology.

- ISI era is an important part the identity for Dawlat al-Islamiyya – over 15% of the pages in ‘IS media products’ category originate from that period.

- While 10% of PDF were encrypted, most documents were produced using tools easily available on most modern laptops.

- Not one of the texts envisages a ‘Jihadist Utopia’ nor proposes a ‘Utopian narrative’. The idea of a ‘Utopian Narrative’ is an artefact of Western misinterpretation. It is not rooted in the texts of of Dawlat al-Islamiyya nor their predecessors.

- Graphics on the documents – not so the content – is availabe in the previous post.

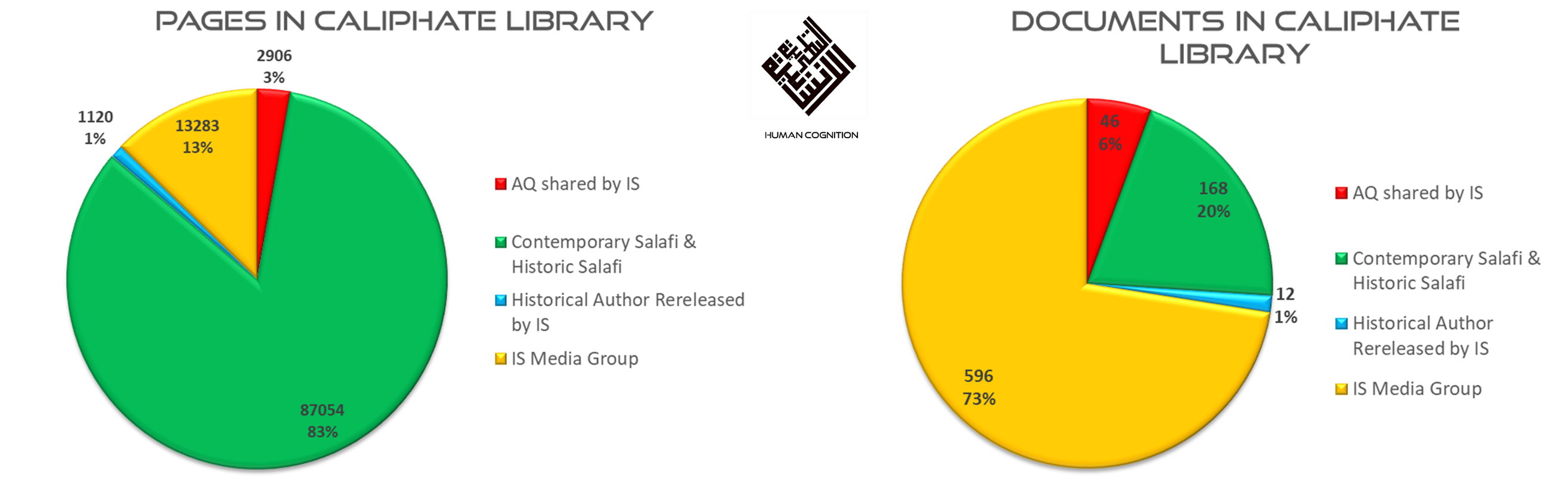

Sample Set taken of the Telegram IS channel “Library of the Caliphate” – more ISIS poroduced articles then historical and contemporary extremist books shared (left) yet the number of pages (right) outweigh what terrorist groups produce.

The pie-chart on the left shows the number of pages of each category. The categories are:

- AQ era (without ISI) in red;

- IS media group in yellow;

- Extremist Salafist books by contemporary and historical authors in green. These writings are neither banned nor illegal in most countries around the world and provide the religious ecosystem to degrade humans and define the ‘other’ as enemy and so forth. The number of pages of these writings outweigh what terrorist groups produce.

- Blue shows the dedicated re-publication of such legal extremist Salafist writings by IS’ Maktabat al-Himma, marking the importance for the extremist constituents.

The pie-chart on the right side shows the quantity of documents in the Caliphate Library. 596 uniquely IS (and ISI) produced document make up over 13,000 pages. Hence, the number of IS produced documents are shorter, quicker to read, more in number, yet reference to the rich ecosystem of the (green) 87,000 pages of extremist Salafist writings.

The AQ Era – The Arab Peninsula Documents

6% of the 908 PDF documents are from the AQ era, excluding the Iraqi AQ side, The Islamic State of Iraq, the forerunner of IS. It is significant to note, for IS and their readership, the ‘historical’ AQ documents of the Arab Peninsula jihadist ecosystem matter. It provides the theological legitimacy to kill fellow Sunni Muslims in the service of Arab regimes (i.e. al-Zahrani), the historical jihadist legitimacy of indiscriminate killings (i.e. al-Fahd[8]) or the re-enforced intellectual argumentations of fighting jihad until the end of times (i.e. al-‘Uyairi[9]). The first generation of al-Qaeda on the Arab Peninsula (AQAP) had been pioneers in facilitating the Internet as a constant medium for their output in the early 2000s and had a major crossover to the unfolding jihad in neighbouring Iraq. AQAP not only produced the first electronic jihad magazines but also had been key and cornerstone to develop the Sunni jihadist online activism.[10]

Of these core pre-IS AQ documents one AQ author is dominantly featured: Abu Hummam Bakr bin ‘Abd al-‘Aziz al-Athari. Al-Athari gained fame by his real name: Abu Sufyan Turki bin Mubarak bin al-Bin’ali, who had been a keen supporter of the Islamic State in Iraq when it was part of AQ and later sided with al-Baghdadi before falling out with him.[11] He was a prolific writer and, for example, under his pseudonym eulogized the Islamic State of Iraq leaders, the “believer of the faithful and his minister”, Abu Omar al-Baghdadi and Abu Hamza al-Muhajir in April 2010. His writings regarding the Arab Spring in 2011, calling for violence as the only possible means in Syria[12] are shared by the Library as well. A document from February 2010 entitled “Conversation or Mooing”[13] is shared as well, highlighting the framework of that time when the West sought to engage moderate Islamic forces to undermine extremist groups – whereas this document shared in this context almost ten years later is seen as proof for the Caliphate Library target audience that ‘true’ Islam is victorious despite the odds. His 2011 fatwa styled ruling on banning women from driving is also part of the collection and was enforced during the reign of IS during its physical territorial phase in Syria and Iraq.[14]

Other writings of the AQ era feature Nasir al-Fahd, a treatise on “What a Woman should wear in front of other women”, dated to the year 2000. Nasir al-Fahd was a prominently featured scholar among the ecosystem and his writings among other things called for indiscriminate revenge bombings of citizens of enemy nations and the like. Nasir al-Fahd was arrested after the May bombings 2003 in Riyadh and recanted his support of terrorism while in prison. AQ, at that time active in Saudi Arabia, was keen to support al-Fahd by the emergent online ecosystem at the time and al-Fahd’s alleged letter “recanting the alleged recantation” was featured within this ecosystem.[15] Unlike al-Fahd, Abu Jandal al-Azdi was executed by the Saudi state after his arrest in August 2004. Abu Jandal al-Azdi aka as Abu Salman Faris al-Zahrani by his real name, was a key jihadi-theologian. In the Caliphate Library collection his work on “Usama bin Laden – Reformer of our Time and Crusher of the Americans” (640 pages) is featured and a new IS version of his early 2000s writing regarding the permissibility to kill Muslims in the service of Arab nation states had been re-published. He was on a wanted list of Saudi Arabia, to which AQAP responded by issuing a 65 page long ‘counter-narrative’ featuring the 26 individuals. This writing was edited by al-Azdi and is part of the Caliphate Library.

The Documents of the precursor Islamic State of Iraq (ISI) and IS

In addition to the material produced by IS, the channel republished ISI era documents. This is an important part of the identity for Dawlat al-Islamiyya (IS) and a religious authoritative source – over 13% of the pages (over 13,000) in ‘IS media products’ category originate from that period. Most documents are martyr stories that had been published by the AQ Iraq media diwan (2005) and was then distributed by the Majlis al-Shura al-Mujahidin and al-Furqan, the foundations of ISI. IS re-published these early martyr stories of Iraq fighting against mainly the Americans in 2018. The document of 235 pages features over 50 martyr stories, including prominent al-Zarqawi lieutenant Abu Anas al-Shami[16], valuing the avant-gardist jihadist operations of the time that led to the success of the Islamic State a decade later. The textual cohesion laid by such martyr stories of the ISI-era is continued by similar stories by, for example, IS’ al-Rimah media featuring the martyr Abu ‘Ali al-Shammari, a member of a large tribe, from Iraq, following the “examples of Khattab [Samir Saleh ‘Abdallah, Chechnya], Shamil [Basayev, Chechnya], Usama [bin Laden] and other” jihadi foreign fighters.[17] A focal point, naturally, are the IS era documents that to a degree are transcripts of IS radio al-Bayan programs, featuring lengthy theological explanations by iconic IS figures such as Abu ‘Ali al-Anbari outlining the Sunni jihadist understanding of being a muwahhid, of professing the meaning of the “oneness of God”.[18] Other key documents include the series about the “Bath party – it’s history and ideology” (al-Battar), the treatise “legal ruling on defending against an attack against the Islamic shari’a and the ruling of the [jihadist] banner”, an updated re-print from the Saudi AQ era and released by al-Battar in 2015. The collected speeches by Abu Muhammad al-‘Adnani are likewise featured with IS Maktabat al-Himma re-releases of slain ISI leaders writings, prominently having featured the “30 recommendations to the amirs and soldiers of the Islamic State” by ‘Abd al-Mun’im bin ‘Iz al-Din al-Badawi aka Abu Hamza al-Muhajir. This 74 page long advise, in the sense of his legacy, was re-distributed in multiple languages by Maktabat al-Himma in 2016. Several Arabic articles translated from English released in English in Dabiq appear alongside selected articles taken from the weekly al-Naba’ magazines. Showcasing the active side of the Islamic State, the constant emphasize that jurisprudence during their reign was actively implemented, lengthy documents clarifying everyday legal issues are part of the library, explaining in a Q&A styled process legal rulings (fatwa) to mundane issues such as who has to recompense what to the family of a victim of traffic accidents or general rulings in regards of blood money and revenge killings.[19] Ashhad writings on the proper process during Ramadan[20], reacting to AQ claims and drawing a line of distinction between AQ under bin Laden and that of al-Zawahiri[21] and classical jihadist-styled theological treatises that in sum can be labeled as anti-democracy analysis.[22]

Not one of the texts envisages a ‘Jihadist Utopia’ nor proposes a ‘Utopian narrative’. The idea of a ‘Utopian Narrative’ is an artefact of Western misinterpretation. It is not rooted in the texts of IS nor their predecessors.

The Salafist Distributions by Maktabat al-Himma

While the majority of single PDF documents are crafted by the two dominant Sunni jihadist groups AQ and IS, the Caliphate Library distributed historical and contemporary Salafi writing which intersects with modern Sunni jihadist theology. Earlier writings through Maktabat al-Himma, a theological driven publication house of IS republish writings by authors of the ‘Abd al-Wahhab family, mainly Muhammad bin ‘Abd al-Wahhab. His writings are the backbone of modern-day Wahhabism that constitutes the state doctrine of Saudi Arabia and had been radical-revolutionary at his time. Banning veneration of graves and being outspoken anti-Shiite, the work of ‘Abd al-Wahhab gave birth to modern jihadism where a clear Sunni identity is laid out in cohesive literal format and with the Islamic State 2013 onwards, demonstrating the power of applying this form of extremist theology in audio-visual format to appeal to a less text-affluent zeitgeist on the Internet. Apart from extremist Salafist books re-published through Maktabat al-Himma (MH), using own created covers featuring the MH and IS logo with the slogan “upon prophetic methodology” many Salafist writings shared by the Library channel are scans made available as PDFs.

Maktabat al-Himma, IS core textual media foundation, distributes historical writings by Muhammad ‘Abd al-Wahhab to boost and promote their actions as theological sound based on the writings of the founder of Wahhabism.

Of the non-IS branded Salafist writings shared by the Library, not all works are to be associated with the extremist segment. The 40 hadith by al-Nuwawwi for example are an exception and are often simply party of any well stocked Islamic library. What makes the Salafist writings shared by the Library to be defined as extremist, however, is set on two principles:

- The Salafist writings are linked to modern jihadist groups based on the shared theology, using the same language and referencing oftentimes the same religious sources to justify violence. Legitimizing killing those who insult prophet Muhammad (ibn Taymiyya 1263-1328 AD) is put into practice by AQ in the 2000s (following the Muhammad cartoons), sanctions the murder of Theo van Gogh (Amsterdam, 2004) and the main theme of a major ISI/IS themed video series (2012-2014). The writings are the basis of modern jihadist theology, relating the jihadist religiosity to violence against the defined ungodly, unholy or simply unhuman ‘other’.

- Writings such as Minhaj al-Muslim featured in the Library are heavily cited by AQ and IS. Looking at the Arabic produced content of jihadist groups allows to reference and link the sources. The Caliphate Library Telegram channel provides a comprehensive collection of such core-jihadist historical and contemporary extremist Salafist textbooks that continue to inspire and fuel the Sunni jihadist movement as such. This is not limited to historical Salafist writers such as of ‘Abd al-Wahhab, ibn al-Qayyim, but includes modern extremist Salafist thinkers who are as outspoken in their works.

The Extremist Salafist Connection

The Salafist books featured in the Caliphate Library Channel by far outweigh in number of pages the jihadist documents. Apart from classical works by Imam Shawkani or Ibn al-Qayyim, the “shaykh al-Islam”, Ibn Taymiyya is overrepresented. Ibn Taymiyya, died 1328, was a prolific writer and member of the Hanbali school of jurisprudence. His work has influenced the Wahhabi movement of which the theological jihadist branch is the most extremist extension thereof. Within the 300,000 penned pages by AQ authors and IS productions, Ibn Taymiyya is referenced over 40,000 times. His jurisprudential (fiqh) works justify the persecution and killing of non-Muslims and provide a clear-cut definition of when Sunnis become apostates – the very essence of almost every contemporary jihadist author (and applied in the videos of jihadist groups). Ibn Taymiyya is renowned for his “characteristically juridical thinking”[23] and has a high level of competence as a legal scholar expressed in his writings that are based – at least in parts – on Islamic jurisprudence (fiqh).Ibn Taymiyya is frequently cited in Sunni extremist, writings since the 1980s and accordingly referred to and quoted by jihadist ideologues in audio-visual publications. The “Islamic State” is basing all of its audio-visual output on the theology that has been penned by AQ since the 1980s – with the significant difference, however, that IS has had the territory to implement and enforce this corpus of theology upon the population of the self-designated “caliphate” – which as of 2019 serves as the filmed legacy and pretext for the return of IS. Featured in the Caliphate Library is the over 4,000 page long multivolume “tafsir shaykh al-Islam”, the exegesis of the Qur’an by Ibn Taymiyya and his notorious book “The drawn sword against the insulter of the Prophet” (al-sarim al-maslul didda shatim al-rasul). Within the Sunni extremist mindset, the sword must be drawn upon anyone who opposes their worldview and specific interpretations of Qur’anic sources, the hadith (sayings and deeds of Prophet Muhammad) or frame of references that have been penned since the 1980s. Ibn Taymiyya’s book has been used by Muhammed Bouyeri to justify killing Dutch filmmaker and Islam critic Theo van Gogh in November 2004 in Amsterdam and is part of a long list jihadist operations in recent years.

“The text details how and why to kill targets, first of all because of insult (shatm, sabb, adhan) of Islam. Bouyeri tried to sever van Gogh’s head with a big knife after he had shot him several times. In the text we find the passage: “the cutting of the head without mercy is legal if the Prophet does not disapprove it.” Moreover, the text advises multiple times to use assassination as an act of deterrence. The slaughter of van Gogh in open daylight seems like a one-to-one translation into reality of the directives we find in the text.”[24]

For example, Ibn Taymiyya has been used to justify the suicide bombing attack of the Danish Embassy in Pakistan (2008)[25] after the Muhammad cartoons had been released. In June 2012 the Jund allah (soldiers of God) media outlet of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan published a German language video featuring Moroccan-German “Abu Ibraheem” (Yassin Chouka) calling on his associates in Bonn from Waziristan to kill members of the German rightwing party Pro-NRW.

This exact notion was picked up by German speaking Global Islamic Media Front activists in 2012 in the wake of the violent protests in parts of the Islamic world in response to the movie “Innocence of Muslims.” A German translation of al-Maqdisi’s pamphlet, presumably by Austro-Egyptian jihadist Muhammad Mahmud, enriched the fatwa by the Egyptian pro-jihadist Ahmad ‘Ashush calling for the death of anyone involved in the movie project.[26]

In January 2015 two brothers, apparently trained by al-Qaeda on the Arab Peninsula in Yemen, attacked the offices of the French satire magazine Charlie Hebdo. The Kouachi brothers after the massacre are seen and heard in one video made by a bystander shouting “we have avenged the Prophet” (li-intiqamna al-rasul), and then shoot wounded French police officer Ahmad Merabet in the head.[27] A video published on January 11, 2015 by the IS affiliated media outlet, Asawitimedia, praises the attacks. The video is entitled “The French have insulted the Prophet of God – thus a merciless reaction.”

To cite Rüdiger Lohlker once more: “without deconstructing the theology of violence inherent in jihadi communications and practice, these religious ideas will continue to inspire others to act, long after any given organized force, such as the Islamic State, may be destroyed on the ground.”[28]

This applies not just to deconstructing the massive literature corpus produced by Sunni Jihadists. Without understanding the linguistic-theological links to the extremist Salafist spectrum that is of intimate importance to the modern Jihadist movement, and taking steps against the maintained presence of extremist Salafist materials online (as well as the multilingual printed offline global dissemination), the threat of the most extreme form of religious terrorism is unlikely to diminish any time soon.

[1] Nico Prucha, The Context of the Manchester Bombings in the Words of the “Islamic State” on Telegram, onlinejihad, August 2017, https://onlinejihad.net/2017/08/27/the-context-of-the-manchester-bombings-in-the-words-of-the-islamic-state-ontelegram/.

[2] Paz, Reuven. “Reading their lips: the credibility of jihadi web sites as ‘soft power’in the war of the minds.” Global Research in International Affairs Center, The Project for the Research of Islamist Movements 5.5 (2007).

[3] Brown, Katherine E. 2011. “Blinded by the Explosion? Security and Resistance in Muslim Women’s Suicide Terrorism,” in Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, eds. Women, Gender, and Terrorism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 194-226.

[4] Rüdiger Lohlker, Why Theology Matters – The Case of ISIS, Strategic Review July –September 2016, http://sr-indonesia.com/in-the-journal/view/europe-s-misunderstanding-of-islam-and-isis

[5] Both references, jihad by the sword as well as the tongue are based on Ibn Taymiyya’s understanding thereof, whereas Ibn Taymiyya declares “jihad by one’s hand, heart, and tongue.” Ibn Taymiyya, Qa’ida fi l-inghimas al-‘adu wa-hal yubah? Riyadh: Adwa’ al-salaf, 2002, 19. The first generation of al-Qaeda on the Arab Peninsula (AQAP) referenced the “tongue” as part of the overall endeavor to commit themselves to God and using violence to deny the application of man-made laws: “We call all Muslims to work on behalf of the religion of God, and to jihad on the path of God, by dedicating one’s live, financial abilities and one’s tongue.”

“Statement by the mujahidin on the Arab Peninsula regarding the latest declarations by the Ministry of Interior”, translated and commented in Nico Prucha, Die Stimme des Dschihad – al-Qa’idas erstes Online Magazin, Verlag Dr. Kovac: Hamburg, 2010, 137-144.

[6] Ali Fisher, “Netwar in Cyberia: Decoding the Media Mujahidin”, CPD Perspectives on Public Diplomacy, (Paper 5, 2018) https://www.uscpublicdiplomacy.org/sites/uscpublicdiplomacy.org/files/Netwar%20in%20Cyberia%20Web%20Ready_with%20disclosure%20page%2011.08.18.pdf

[7] Rüdiger Lohlker, Why Theology Matters – The Case of ISIS, Strategic Review July –September 2016, http://sr-indonesia.com/in-the-journal/view/europe-s-misunderstanding-of-islam-and-isis

[8] Nasir al-Fahd, a long-time sympathizer and endorsed by the classical AQ, currently imprisoned in Saudi Arabia.

[9] Yusuf al-‘Uyairi, former bin Laden bodyguard and key AQAP theologian whose writings are in parts of analytical sobriety and in other parts clear theological instructions. His writing “constants on the path of jihad” is one of the most important documents and was indirectly cited by IS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi when he re-iterated that “god commands us to wage jihad, he did not order us to win”, emphasizing jihadist motivation in this world is to strive to be certified to enter paradise in the next.

[10] The range of pioneer activist media operations spanned from re-thinking jihadist videos to professionally broadcast the testimonies of suicide bombers, include important textual sources in filmed documents to legitimize beheadings (before these became a symbol in Western mindset for AQ Iraq with the filmed beheading of Nick Berg 2004), and even a first form of streaming: a squad of AQAP operatives maintained a cellphone connection allowing an audio recording as the operation unfolded. This audio was then included in a later video production to praise the attack and commemorate the killed operatives. Nico Prucha: Die Stimme des Dschihad – al-Qa’idas erstes Online Magazin, Dr. Kovac: Hamburg, 2010.

[11] Falling out over takfir issues – killed – link

[12] Al-Bin’ali (al-Athari): Ya ahl al-Sham inn al-asima fi l-husam, Minbar al-Tawhid wa-l Jihad, 2011.

[13] Al-Bin’ali (al-Athari): Hiwar am khuwar?, Minbar al-Tawhid wa-l Jihad, 2010. He notes the term khuwar “mooing sounds” by citing the Lisan al-‘Arab reference of the Qur’an: 7:147

[14] Al-Bin’ali (al-Athari): al-Ishara fi hukm qiyyada al-mara’t al-siyyara, Minbar al-Tawhid wa-l Jihad, 2011.

[15] For more on the online operations and key players of the first generation of AQ in Saudi Arabia: Nico Prucha: Die Stimme des Dschihad – al-Qa’idas erstes Online Magazin, Dr. Kovac: Hamburg, 2010.

[16] Abu Anas al-Shami was a renowned theologian and a vital figure for al-Zarqawi and his group. He died in a targeted missile strike by American forces in 2004 near Abu Ghraib in Iraq. He was a Palestinian based in Jordan. He grew up in Kuwait, where arguably many Palestinian workers and engineers had been exposed to the strict teachings and interpretations of the Wahhabi dominated Arab Peninsula Islam. Experiencing war and expulsion again, the Palestinian migrants, who nevertheless had been refugees in Jordan and had come to Kuwait in pursuit of economic opportunities, had to flee back to Jordan because of the Iraqi aggression against Kuwait in 1990, taking the Arab Peninsula Salafism with them. As the PLO sided with Saddam Hussein, the Palestinians lost their base in Kuwait and in most cases returned to the refugee camps of Lebanon, Syria, Jordan and elsewhere. Hazim al-Amin, Al-Salafi al-yatim – al-wajh al-Filastini li “l-jihad al-‘alimi” wa-l “Qa’ida”. Beirut-London: Dar al-Saqi, 2011, 114-127.

[17] Abu Mu’adh al-Shammari, Qissa shahid min ard al-‘Iraq Abu ‘Ali al-Shammari, Rimah Media, 2018.

[18] For example, the – as featured in the library as of time of writing – 26 transcribed episodes of al-Anbari’s lessons how to avoid involuntarily shirk (‘polytheism’).

[19] i.e. Fatawa ‘abr al-athir: Qatl wa-mawt wa-qisas wadiyyat wa-l jana’iz, al-Bayan, 2017.

[20] Abu ‘Ammar al-Ansari, al-Khuttab al-madhbariyya istiqbal Ramadan, Ashhad, 2018.

[21] Abu l-Bara’a al-Yamani, al-Radd al-qasif ‘ala shuyukh al-qa’ida al-khawalif, Ashhad, 2018.

[22] Abu Mu’adh al-Shammari, al-Dimukratiyya wa-atiba’uha fi mizan al-shar’i, Ashhad, 2018.

[23] Wael b. Hallaq: Ibn Taymiyya against the Greek Logicians. Translated with an introduction by Wael Hallaq, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993, xxxiii.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Al-Qaeda claimed responsibility for a suicide bombing attack on the Danish Embassy in Pakistan in 2008. In video entitled al-qawla qawla al-sawarim, “the words [are now about action and hence] words of the sword”, shows the testimony of the suicide operative identified as a Saudi by the nom de guerre Abu Gharib al-Makki [the Meccan]. The one hour long video justifies the attack – among a rich blend of theological narratives – by the referencing of the time to talk is over, the time for actions (i.e the swords must be drawn) has come to avenge the insults of Prophet Muhammad, referring to the work of Ibn Taymiyya.

[26] Nico Prucha, Fatwa calling for the death of the director, producer, and actors involved in the making the film “Innocence of Muslims”, Jihadica, September 18, 2012, http://www.jihadica.com/fatwa-calling-for-the-death-of-the-director-producer-and-actors-involved-in-making-the-film-%E2%80%98innocence-of-islam%E2%80%99/

[27] A detailed oversight is provided by the BBC, outlining in depth also the attack by IS member Amedy Coulibaly who executed several hostages in a Jewish supermarket, http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-30708237

Amedy Coulibaly uploaded a video where he pledges allegiance to al-Baghdadi. Part of his video is used in one of the ‘official’ IS videos to applaud the January 2015 Paris attack, Risala ila Fransa, Wilayat Salah al-Din, February 14, 2015.

[28] Rüdiger Lohlker, Why Theology Matters – The Case of ISIS, Strategic Review July –September 2016, http://sr-indonesia.com/in-the-journal/view/europe-s-misunderstanding-of-islam-and-isis