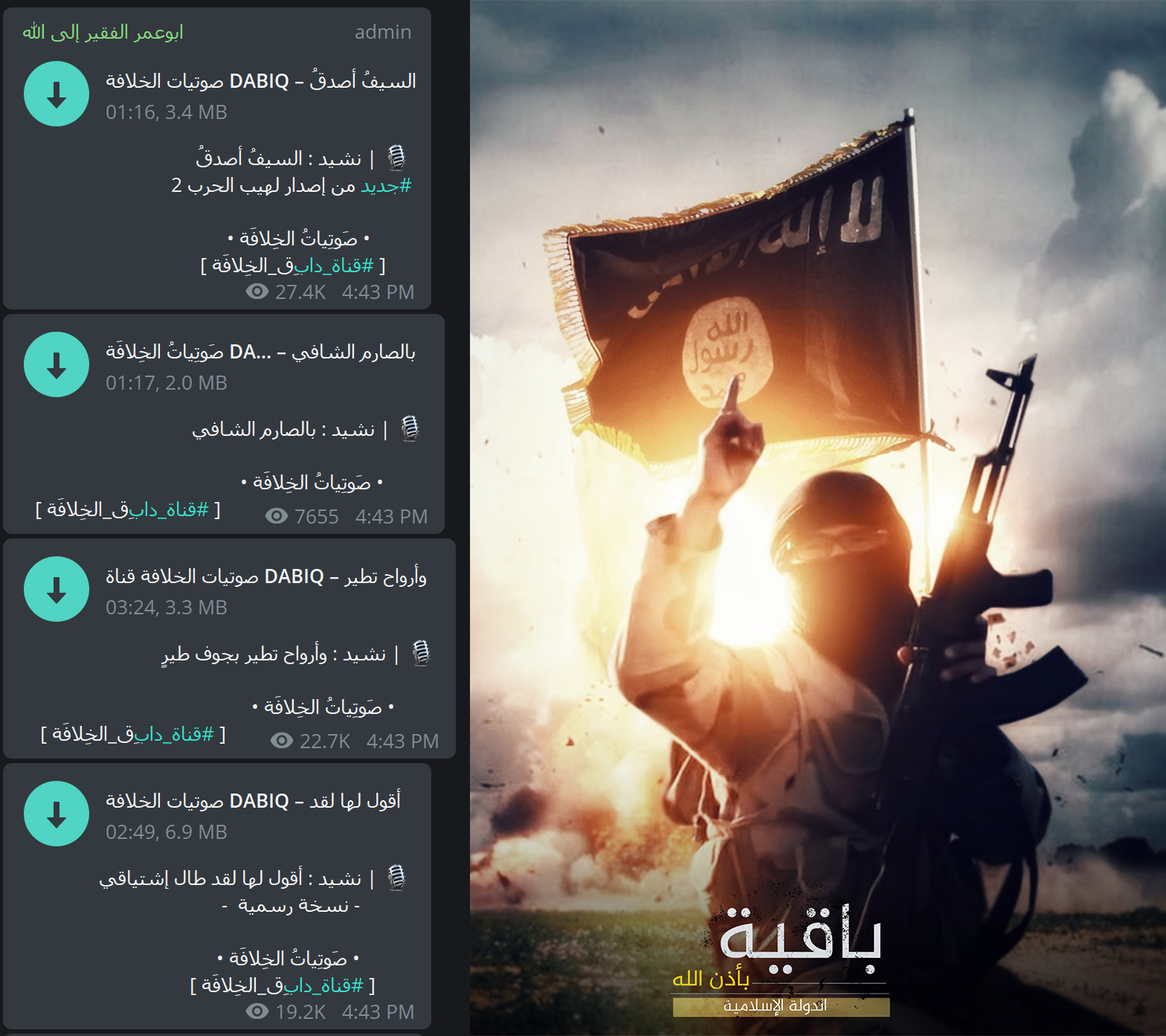

Note: A version of this article was originally published in 2007 by the Journal for Intelligence, Propaganda and Security Studies. Due to the up-to-date nature of what type of content jihadists create, curate, disseminate and of course share via online (and offline networks), the article is slightly reworked republished here. The work by Faris al-Zahrani, a core member of the first generation of AQAP and it’s electronic da’wa networks that serve as a theological-activist legacy foundation for both AQ and IS, is a valuable cornerstorne in understanding jihadism in their own (Arabic) words. His work is shared on Telegram, sometimes in it’s original release format, sometimes in a more timely package, and his interview for the Sawt al-Jihad is a legend within jihadist circles online. Abu Jandal al-Azdi, as he was known by his nom de guerre, was al-Qa’ida’s editor and a muscle of online jihadi activism as coined by the marvelous Joas Wagemakers, one of the few scholars in the field of jihadism who actively reads Arabic content to make sense of the vast content released by extremist actors & groups.

(above: 2018 Telegram screenshot of a group conveying English materials to provide da’wa to non-Arabic speakers in the jihadist understanding of pedagogy; this group shared old-AQ and – at the time – new IS materials)

2007: The Internet has become the medium of communication and exchange of information for the Jihadis. In the past years, the Internet has been increasingly used on a very efficient and professional basis. Countless online Jihad communities have come into existence. Not only have a number of online forums been established[1], but there are countless blogs and traditional websites available, which spread and share a broad variety of documents and data in general. Jihadis often refer to the Arabic term isdarat for data, that consists of general publications, videos (suicide bombings and last testimonies, roadside bomb attacks etc.), sermons or general statements and declarations – but also technical information such as bomb-making, weapons guides or chemical crash courses[2]. Over the years the Internet has become a 24-hour online database, where any user with sufficient knowledge of the Web (and some Arabic[3]) is able to access and/or download these isdarat. In an interview with al-Qa’ida’s first online magazine (2003), Sawt al-Jihad (Voice of Jihad), Abu Jandal al-Azdi explains the reasons for these isdarat and states that „these [isdarat] guide the youth of Islam and they [the Mujahidin and their leaders] have published books, statements, audio-files, and videos.”[4] Today the users exchange useful tips and practical hints, discuss ideological and theological issues and allow an insight into their tactics and strategies within the online forums. The usage of the Web has been systematically funneled by the al-Qa’ida cells on the Arabian Peninsula.[5] To provide a short overview on what kind of isdarat are being spread over the Internet here are several categories (letzter Halbsatz unklar-passt es so?)[6], roughly comprising, what I would call world-wide Online Jihad:

- Handbooks: Explosives – how to fabricate, how to use (for example RDX, TNT or IED’s and practical tips from battle-tested Mujahidin); Weapon handbooks – nearly all weapons categories are described, such as anti-tank cannons, assault rifles, rockets; ABC weapons – explanations and theoretical discourses; Military handbooks – translated U.S. Army material as well as handbooks designed for urban and guerrilla warfare; Toxins, Assassinations, Intelligence and counterintelligence, etc.

- Technical assistance (hard-, and software), using the Internet – essential information such as how to program, design and maintain a web page, how to make videos and what file-hosting-sites are best used (and porn-free) to host these sometimes 1 or 2 GB-size files; Programs, what programs should be used to protect oneself, to conceal the IP address, Firewall, Anti-Virus etc.; another important aspect is the use of PGP, the encryption software, that has led to the development of „ the first Islamic program to communicate secure over networks.”[7]

- Ideology – Ranging from statements, letters, books and comments from Osama bin Laden, to very detailed and thoroughly described would-be legal documents (fatwa’s) [8] and documents in general that deal with all kinds of religious or practical justifications and explanations. These sometimes several hundred pages long WORD and/or PDF documents include topics such as „Guiding the Confused on the Permissibility of Killing the Prisoners”[9], referring to the capture of seven Russian police officers in Chechnya who were later executed; the call to join, or a call for Jihad, as written by Abdullah ‘Azzam in his prominent document entitled „ Join the Caravan!”[10] or the writings of al-Maqdisi, who is currently imprisoned in Jordan and who regularly denounces democracy and democratic elections as being un-Islamic and therefore kufr (disbelief)[11], are circulating on the Internet and are being read by mostly those who also are participants (active and passive) in the numerous online forums.

Shared by AQ groups online 2000s

The Internet has become essential to understand (and identify) the ideology of al-Qa’ida and other radical islamic currents. With the creation of online databases, the ideological documents are now available for everybody. The Jihadis have undertaken the endeavour of digitalising a great deal of writings that played a major role in the 1980s Jihad against the Soviets (Abdullah Azzam) and have influenced a generation of radicalized youth, who then continued this tradition – only this time using laptops and the Internet.

Most authors of ideological documents – as listed above – usually entitle themselves as being a Shaykh, a respected and knowledgeable man, who has either studied at a Islamic university and specialized in sharia law or other fields of Islam, or is being called a Shaykh because of his understanding of Islam. Take Yusuf al-‘Ayiri, the ideological predecessor of Faris az-Zahrani (also known as Abu Jandal al-Azdi) and the first leader of the al-Qa’ida organization in Saudi Arabia. Although he never completed secondary school, he has become one of the best-known and famous authors of Jihad literature. He was killed during a clash with Saudi security forces in 2003, but has since his death attained an even more important role and his writings are influencing those, who are interested to find out more about Jihad through the Internet. His writings consist of works such as „The Ruling on Jihad and its [varying] Classes“, „The Truth about the New Crusader War”, or „The Islamic Ruling on the Permissibility of Self-Sacrificial Operations.“ After his death al-Qa’ida started to publish its second online magazine to commemorate al-‘Ayiri, it was called mu’askar al-battar (the Camp of the Sabre), whose nom du guerre had been al-Battar.

The Case of Abu Jandal al-Azdi

Faris az-Zahrani, known by his alias Abu Jandal al-Azdi is an ideologue whose importance and meaning is not much inferior to al-’Ayiri’s. Both ‘scholars’ have added many important documents that are vital for ideological purposes of al-Qa’ida and are crucial for its survival and propaganda. While al-‘Ayiri reappears regularly on the Internet[12], Faris az-Zahrani is a special case even though he has not been as popular as al-‘Ayiri. Az-Zahrani was arrested in Saudi Arabia in August 2004, „while he was preparing a bomb attack on a cultural centre in the town of Abha, in the south of the Kingdom.“[13] Unlike al-‘Ayiri or most of the wanted Mujahidin and ideologues, az-Zahrani, the number 8 on the list of the 26 most wanted jihadis, is alive, serving a prison sentence and has a university degree[14]. He has become known for having written books and essays such as „Bin Laden: The Reformer of our Times and Defeater of the Americans”[15], his book referring to 9/11 „Allahu akbar – America has been devastated”, or „the Dispute [between] the Sword and the Pen”[16] and for his articles in the Voice of Jihad (such as „Pledge them Loyalty until Death”[17]). Az-Zahrani, whose real name was unknown until the release of the „List of the 26 Most Wanted”[18] by Saudi authorities explains in an interview with the Voice of Jihad his reasons for publishing under the alias Abu Jandal al-Azdi, as he compares himself with other prominent ideologues. Beginning with Osama bin Laden (also known as Abu ‘Abdallah, or Abu Qa’qaa’), he refers to other scholars that publish their work using an alias, „since the Mujahidin and their leaders are at war with the Crusaders, the Jews (America and Britain […]) and their agents, the heretics, who are present in our country.”[19] He goes on by mentioning the works of writers and scholars that are available online and it seems that az-Zahrani has read most, if not all, of their work and concludes „the day will come, you will know who is Abu Jandal al-Azdi – I am begging God for firmness until death.”[20].

Unlike the older scholars, the new generation of radical writers are roaming freely on the Internet, having adapted themselves to modern technology, being able not only to read the huge amounts of must-read Jihad literature, but they do not have to fear being arrested while secretly printing or distributing their writings. In an interview with the Voice of Jihad, az-Zahrani reveals how he used the Internet to publish his work and explains the advantage of the Web. Being asked „well known on the Internet is your beneficial book ‘the Scholar on the Ruling of Killing Individuals and Officers of the Secret Police’, could you briefly tell us about the judicial sharia-ruling [that allows] to target the secret police?”[21], Az-Zahrani informs the reader about the second edition of this „most famous book, that is circulating on the Internet, (…) this book provoked [lots of] good reactions among those seeking knowledge and the youth of Islam, and it also provoked severe reactions from the supporters of the idols [the ruling Saudi family].”[22] Books like these and articles of the Voice of Jihad, as for example „the Urgent Letter to the Soldiers in the Land of the Two Holy Places”[23] led to reactions by Saudi counter-terrorist units. Furthermore az-Zahrani delivers a detailed description how his work stirred up the establishment ‘ulama’, the religious scholars of Saudi Arabia who are loyal to the Saudi ruling family, and reflects about the reaction of several Arabic newspapers after one of his students confronted his professor with this work – and was banned from university. „After five days I met the young man, the agonized innocent, and I asked him whether or not he has returned to his studies, he said no. I told him that I will take his matter to the Minister of Education […]., I withdrew the book from the Internet and gave the Minister of wakf (endowment) a copy […], but we never saw any reaction.”[24] Az-Zahrani concludes the first part of the interview by drawing a direct parallel to al-Maqdisi, who wrote the book „Obvious Disclosures of the Disbelief of the Saudi State”[25]. What had been the case with al-Maqdisi happened to az-Zahrani: both had published books using an alias, both attacked the Saudi system and the ruling family, denouncing them as being unbelievers, heretics, stressing that it is the fault of the Saudis, that Americans and Westerners are in the holiest country of Islam and both sparked public debates lead by the establishment ‘ulama’ on national TV.

The capture of az-Zahrani has been a vital blow against al-Qa’ida in Saudi Arabia, just a few months after the death of the newly appointed third leader ‘Abd al-‘Aziz al-Muqrin; the organization lost their leading ideologue as well. Immediately after his arrest, the Voice of Jihad published a „Statement regarding the Capture of Abu Salman Faris az-Zahrani,”[26] clearly defining what may best be termed as re-enacting prophecy.

Re-enacting Prophecy – re-enacting Moses and the „Game of the Pharaohs”

For Jihadis life is full of temptation (fitna) and trials (ibtila’) set by God and only those who are true believers can resist these temptations, remain focused and concentrated on the main objective of human existence – the service of God, Him alone (‘tawhid’). The battle is on against a system of disbelief and heresy, notably led by the U.S. with the help of their agents within the Islamic world, whereas the members of the ruling clan of the Saud family are nothing less than agents of the West. This notion is part of a widespread rhetoric in Jihad literature. Therefore the perception of being imprisoned by Saudi authorities means to be imprisoned by the worldwide system of disbelief, whereas the God fearing, righteous Muslim is suddenly subdued, his belief is endangered and will be tested. The „Statement regarding the Capture” starts with the declaration that „captivity is a milestone of the marks of the path”[27] and „a form of the test, by which God wants to trial the believers and is a ruse of the unbelievers, just as God says: “And when those who disbelieve plot against thee (O Muhammad) to wound thee fatally, or to kill thee or to drive thee forth; they plot, but Allah (also) plotteth; and Allah is the best of plotters.”[28] The statement continues by directly comparing the situation of the Muhjahidin today with Moses, who was sent by God to the Pharaoh and who was – just like the Mujahidin in their perception – persecuted and imprisoned by the infidel ruler. To underline their argument, several verses of the Quran are being cited. Unusual is the fact that most of these verses are taken from the surat ash-shu’ara’ (the Poets), that narrates the stories of the Prophets Moses, Abraham, Noah, Hud, Salih and others. Just like the Mujahidin, Moses was first tempted in prison, then later publicly contested – and beat the Pharaoh by his unique arguments and his ability to counter the magic deployed by the magicians summoned by the Pharaoh.[29] By this he won over the people and the magicians , who subsequently recognized that Moses was sent by God and recognized that Pharaoh is not their Lord and his Gods have proven wrong.[30] This notion probably prospered when the Saudi „government, under pressure because of the violence[31], apparently tried to appease the Jihadis by offering an amnesty period of one month (June – July 2004).”[32] Now, just like the interaction of Pharaoh and Moses, the ruling system, deemed infidel, invited the opponents, the Mujahidin, fighting on the „path of God” to – just like Moses – be opposed by the rulers who activated „specific heraldries, having been able to mobilize armies from their available soldiers (magicians, scholars, authors, journalists and the general media).”[33] If the majority of the Mujahidin and their scholars accepted this amnesty, then they would have been imprisoned because the ruler is aware that he cannot defeat the „arguments of truth” and would thus publicly display his flaws. Since the rulers are aware of that, according to az-Zahrani, there cannot „be a true dialogue with the People of the Truth (= the Mujahidin),” for they, the Saudi government, are „incapable to give answers to the questions by the free Mujahidin […] published on their websites and elsewhere.” The questions are for example:

„What is the ruling on the rulers who do not judge based on what God has revealed (…); what is the ruling on the rulers who decide, based on the laws of disbelief and idolatry, instead of what God has ruled; what is the ruling on the rulers, who permit the inviolable and have forbidden the permissible; what is the ruling on the rulers that wage war on God, His messenger and the believers, using different kinds of techniques, [such means as] enticement and terror; what is the ruling on the rulers that keep the peoples away from the religion of God?”

These questions have not been answered by the Saudi regime. Radical ideologues like az-Zahrani claim to be the bearer of truth with their attacks on the regime, stating that „whoever does not do what they [the Saud family] want, then they will place him in their prisons, and they will torture him, and they will say there is no dialogue with such people except with the rifle and the sword.” The question is not co-existence, but to remove the ungodly ruler and (re-) establish an Islamic caliphate on the Arabian Peninsula, implying the rule of God, the sharia and thus allowing all Muslims, all believers the right path, defined by the strict exegesis of Quran and Sunna. The constant comparison to Moses and the Pharaoh is an ancient comparison to modern times – obeying the ruler and denouncing belief, or resisting the ruler and be imprisoned. And just as Pharaoh had assembled his „magicians”, so will the rulers of Saudi Arabia gather their „magicians” to fight an inevitable battle with the Mujahidin, who will like Moses remain steadfast and resolve this battle victorious.

Quranic verses, taken out of their context and placed to underline the arguments such as 26:29: [Pharao said] „If thou choosest a god other than me, I assuredly shall place thee among the prisoners”, re-affirm the reader (and the writer) of their holy mission, that they cannot be misguided and are struggling not only for the truth but a greater good, namely the Islamic umma. According to al-Zahrani, the „phenomenon of the Pharaoh” is present at all times, throughout history of mankind – manifested by the rule of the Al Saud (Saudi family) on the Arabian Peninsula, the birthplace of Islam. With their writings, ideologues such as Faris az-Zahrani consolidate the conviction of certain circles, that the near enemies, the governments in the Arabic countries are kept alive by the West, if it serves the interest of the West and rule their people not only in a un-Islamic manner but do not tolerate any form of freedom.[34] And freedom for hard-core ideologues like az-Zahrani and others means that their interpretation of the religion of God must be applied.

What has been written about imprisonment, torture, arbitrary use of power, etc, by certain regimes in the Middle East may be true; the mixture of frustration and the obligatory identification of a scapegoat combined with the Islamists conviction that their understanding of Islam is the only permissible school of thought (for all of mankind) has become an attractive alternative to many younger people, not only living in the Middle East.

—

2020 Does the writings by al-Zahrani / al-Azdi still matter?

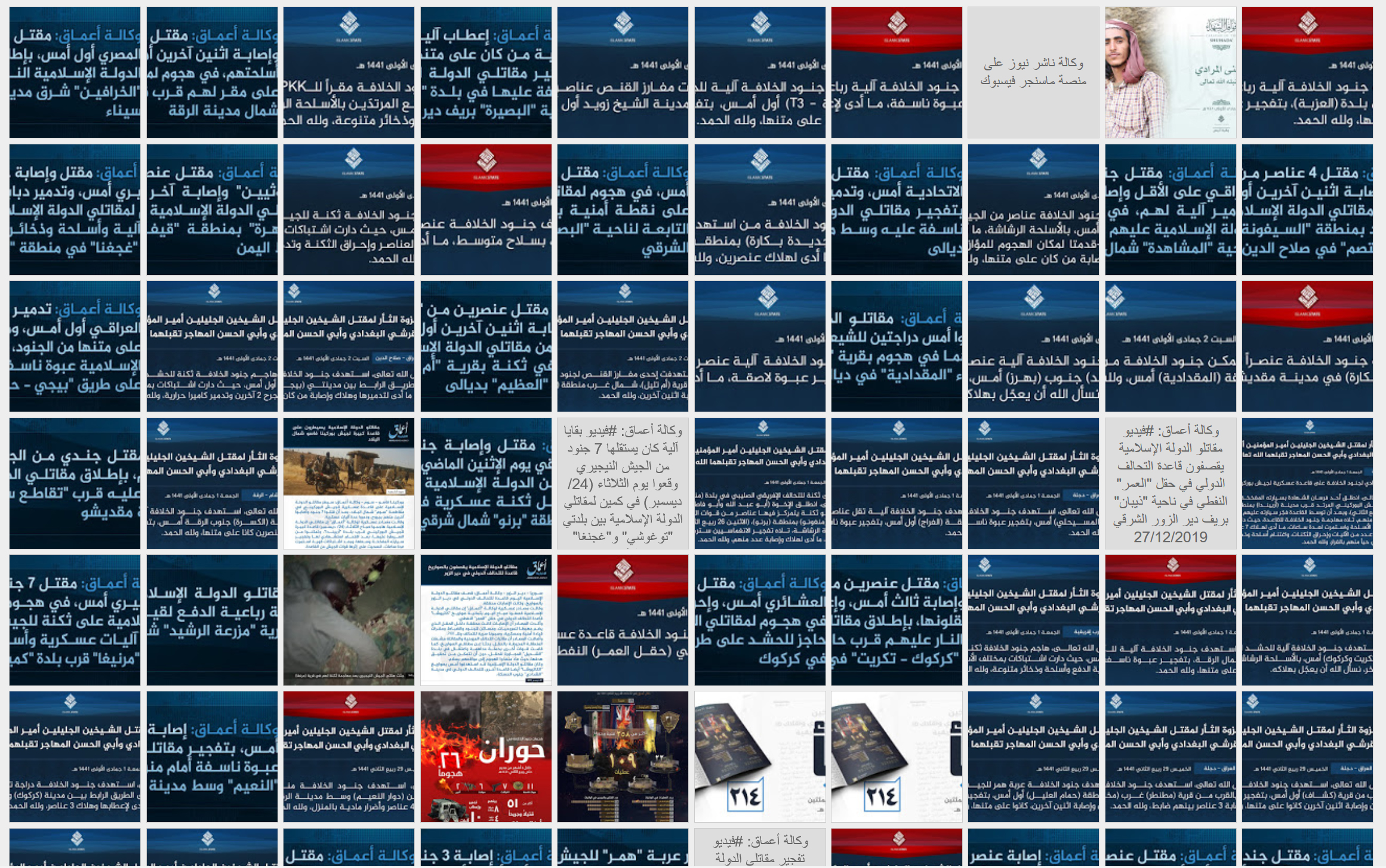

Writings released 2014/5 featured in the context of writings by al-Azdi, having penned “advice to the soldier” whereas 2014/5 IS took this right up to issue a clear (based on AQAP generation output) “ruling in regards of the soldier of the taghut”;

and al-Azdi’s scholarly framed “ruling on killing individuals and soldiers of the secret police”;

and of course the now intensified cross-platform use: IS January 2020 advising to get know al-Azdi using old links (up since 2015) via TamTam.

—-

[1] Most of these forums, which are sometimes falsely described as chat-rooms, are online for several years now. Some of these forums have vanished, others have always been re-established after having been shut down by either authorities, or, as we can observe these days, by individuals who undertake counter-cyberjihadist measures. See for example: http://www.washingtontimes.com/article/20071010/NATION/110100083.

[2] There is countless data on the web – especially in the forums issues such as bomb-making or tips for snipers are being discussed. Sometimes Mujahidin share their field knowledge and sometimes users simply seek the know-how.

[3] The main forums are all Arabic, but forums in other languages (English, Turkish, Russian etc.) are available. The Jihad videos are also sometimes subtitled and quite a few documents have been translated by „brothers of the translation department” into English.

[4] sawt al-jihad number 11, 17.

[5] Al-Qa’ida is subdivided in several organizations (tanzim), each having a specific name, identifying the area of operation; tanzim al-Qa’ida fi-jazirat al-‘arab is the official name for those cells operating on the Arabian Peninsula. Commented translations of all statements and memoranda made by al-Qa’ida on the Arabian Peninsula: Nico Prucha, Die Stimme des Dschihad – al-Qa’ida’s erstes online Magazin (thesis soon to be published).

[6] These few categories shown here as an example, serve to manage and keep track of the loads of growing downloadable data.

[7] This program, called „the Secrets of the Mujahiden” (asrar al-mujahidin), was published online in the forums and has received some attention on the Internet. This program, written by the „Technical Squadron” of the GIMF, the Global Islamic Media Front, is designed to be a secure method of communicating over the Internet, for „al-Qa’ida worldwide, for the Islamic State Iraq, Ansar as-Sunna (…)”, even for the „Islamic Army of Palestine” and the Groupe Salafiste pour la Prédication et le Combat – the GSPC that officially became the Organization al-Qa’ida in the Islamic Maghreb. More prominent is a handbook called „the technical mujahid” (al-mujahid at-tiqqani), that gives a detailed description how to use PGP encryption software (chapter 4), how to hide data within JPEG pictures (chapter 1) and how to fire smart weapons, shoulder-fired rockets at U.S. Army helicopters (chapter 3). For a good insight on the manual: Abdul Hameed Bakier, The New Issue of Technical Mujahid, a Training Manual for Jihadis, Terrorism Monitor, March 29, 2007, http://jamestown.org/news_details.php?news_id=232 (09.10.2007).

[8] Islamic legal documents, issued by the ‘ulama’ (religious scholars). Since al-Qa’ida doesn’t recognize the Saudi ‘ulama’, al-Qa’ida ideologues issue their own fatwa’s, denouncing the Saudi ‘ulama’ as ungodly and therefore claiming to be responsible for the guidance of the Islamic community.

[9] Yusuf Al-Ayiri, Al-hadayat al-hiyara fi-juwaz qatl al-asara – for a description of the writings of this prominent al-Qa’ida ideologue: Roel Meijer, „Re-Reading al-Qaeda Writings of Yusuf al-Ayiri, http://www.isim.nl/files/Review_18/Review_18-16.pdf.

[10] Abdallah Azzam, Ilhaq al-qafila, http://tawhed.ws/r?i=1600 – a detailed commented translation of his article „ Join the Caravan” is provided by Thomas Hegghammer in Al-Qaida Texte des Terrors, ed. Gilles Kepel and Jean P. Milelli (Munich: Piper, 2006), 193-212.

[11] For example: „Useful answers regarding parliamentary participation and it’s election [that are] contradicting the unity of God” (p.10-25) – taken from the „ Fatwa-Collection by Abu Muhammad al-Maqdisi.”

[12] In most forums a new file (19.10.2007) had been posted and ready to be downloaded – a 440 MB-data compilation that comprises al-Ayiri’s writings and speeches, as well the writings of other prominent al-Qa’ida activists (e.g. al-Muqrin) that had been killed by Saudi security forces.

[13] Roel Meijer, The ‘Cycle of Contention’ and the Limits of Terrorism in Saudi Arabia, in Saudi Arabia in the Balance: Political Economy, Society, Foreign Affairs, ed. Paul Aarts and Gerd Nonneman (London: Hurst and Company, 2005), 271-314.

[14] According to Stephen Ulph, „ he was highly trained in fiqh [Islamic jurisprudence] and was a graduate of the Shari’ah College of Imam Muhammad Ibn Saud Islamic University’s Abha branch.” Stephen Ulph, Al-Qaeda’s Ideological Hemorrhage, The Jamestown Foundation, http://jamestown.org/terrorism/news/article.php?articleid=2368409.

[15] For a description of this work: Reuven Paz, Sawt al-Jihad: New Indoctrination of Qa’idat al-jihad, PRISM Series of Global Jihad, No. 8, http://www.e-prism.org/images/PRISM_no_8.doc.

[16] http://tawhed.ws/a?i=9 – a list of most of his publications.

[17] Sawt al-Jihad Number 13, 16-18.

[18] http://www.saudiembassy.net/documents/Wanted%20Poster.pdf.

[19] Sawt al-Jihad number 10, 23.

[20] Ibid.

[21] The intention is of the interviewer is the receive a clear statement by the scholar az-Zahrani, based on the Islamic corpus juris, that allows to actively combat the Saudi authorities, especially it’s agents of the secret police and also the common soldier.

[22] Sawt al-Jihad number 10, 26.

[23] Sawt al-Jihad number 16, 21-26 defines the soldiers in the service of the authorities as being apostates (murtadin), who are being used by the Saudi government and the Crusaders as executioners. „ If you do not obey those [Saudi] ‘ulama in resisting God, there is no doubt that you are not just guilty of disobedience [to God], but of apostasy from Islam (…). You are not assisting the Crusaders in a few words, you have assisted them by yourselves (…), why don’t the Crusaders come by themselves to kill the Mujahidin!!!”

[24] Sawt al-Jihad number 10, 26.

[25] http://tawhed.ws/r?i=2

[26] Sawt al-Jihad number 22, 5-6.

[27] Referring to the work Milestones by Sayyid Qutb (ma’alim fi-t tariq).

[28] Quran 8:30, translation by Mohammed Marmaduke Pickthall, http://www.sacred-texts.com/isl/pick/index.htm.

[29] Quran 26:30-38 (Pickthall).

[30] Quran 8:50(Pickthall).

[31] In 2004 the Jihadis had targeted several Western oil companies and killed five Western workers in the Red Sea city of Yanbu.

[32] Al-Rasheed, Contesting the Saudi State Islamic Voices from a New Generation (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 190.

[33] Abu Jandal Al-Azdi, A Program We won’t show you except what the Al Sa’ud perceives and the Al Sa’ud doesn’t Guide you to anything else than to the Path of Reason, http://tawhed.ws/r?i=1823. This document is also known by the title the Game of the Pharaohs.

[34] A common theme in the jihadi literature, and thoroughly described in “The Statement of the Mujahidin on the Arabian Peninsula concerning the last declarations of the [Saudi] Ministry of the Interior” that calls for the fight against the rulers as being a jihad for freedom, against tyranny and oppression; Sawt al-Jihad number 2, 33-35.