The Islamic State, which is oftentimes referred by its Arabic acronym Daesh, proclaimed the re-establishment of the Caliphate with Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi as Caliph. Daesh stands for al-dawlat al-Islamiyya fi l-‘Iraq wa-sh Sham. The name change reflected the expansion of the Islamic State of Iraq into Syria and since 2014 often refers to itself as the Islamic State or the Islamic Caliphate State. It had been groups such as al-Qaeda (AQ) that theorized about restoring a Islamic State[1] with partially having been able to establish proto-states,[2] but never to the extent of having been able to assert control over a greater population within traditional core Arab Sunni territory. Jihadists had fantasized about being able to combat Arab regimes in the Middle East and North Africa, urging in their rhetoric to be empowered to liberate Palestine, as in their perspective, they had just defeated the Soviet Union with the withdrawal of the Red Army from Afghanistan.[3] Not seeing, yet hoping, in 1989 that one day jihad can be waged inside Arab countries, ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam wrote: “From the morning into the middle of the night, and we are like this, if we have liberated Afghanistan tomorrow, what will we work on? (…) Or God will open a new front for us somewhere in the Islamic world and we will go, wage a jihad there. Or will I finish my sharia studies at the Islamic University in Kabul? Yes, a lot of the Mujahideen are thinking about what to work on after the jihad ends in Afghanistan.”[4] Jihad further internationalized as the zones of conflict diversified. In the 1990s conflicts arose featuring jihadist groups in Bosnia, the Caucasus, prominently Chechnya with jihadist revenge operations throughout Russia, Somalia, it continued in Afghanistan with the Taliban taking over the country and time and again Kashmir. None of these regions of conflict are part of the Arab world, yet from all of these conflicts Arabic-language media items originated, featuring a range of languages, yet dominated by Arabic. Non-Arabic fighters and tales had been subtitled in videos or released as translations, and Arabic native speaking foreigners had been either in key positions (i.e. Khattab) or Arabic affluent local fighters gave their testimony. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that AQ was able to manifest in Saudi Arabia (AQAP) for a few years but the game-changer for Sunni jihadis had been the American occupation of Iraq in 2003. Even when the first generation of AQAP failed, and was forced to re-establish itself in Yemen, jihad was finally able to gradually establish itself in Iraq in the chaotic aftermath of 2003 – giving birth over time what would be known as ISIS. Finally, after the AQAP 1.0 phase where jihadis fought inside Saudi Arabia, referred to as the land of the two holy sanctuaries, and where Arabic was the common language with few exceptions, a Sunni jihadist arm was able to persist in Iraq and produce almost exclusively materials in Arabic featuring Arabic native speakers – to seek to attract more recruits to their cause.

As the late Reuven Paz wrote in 2005, “viewing the struggle in Iraq as “return home” to the heart of the Arab world for Muslim fighters after years of struggle in “exile” in places such as Afghanistan, Bosnia, and Central Asia.”[5] Building a media heritage and tradition, Muslim fighters, referring to the first and early foreign fighter generation had been keen to write about their experiences in “exile” and document their “struggle” by releasing writings, martyr stories, audio-recordings and most important – and on a more regular basis – videos. Especially written accounts of the shuhada’, the martyrs, had been a popular and a unifying element of all conflict zones where foreign and local fighters presented their struggle as a fight for justice and their cause as decreed by God on his path. Increasingly – and as early as the early to mid-1990s – this form of documented “struggle” in “exile” entered the Internet where it is meant to stay and continues to inspire individuals to this day.[6] The martyr-stories are an integral part of the jihadist literature. Documents in Arabic outline individual biographies from 1980s Afghanistan[7] to the 1990s Chechnya[8], Bosnia[9], Somalia, to the 2000s with Afghanistan[10], the Caucasus, Somalia, Saudi Arabia[11] and Iraq[12]. From every region, from throughout the 1980s (Afghanistan) to the 2000s, Sunni extremist militant groups used the media as a tool to report to fellow Muslims (mainly in Arabic but not exclusively) about their – in their view – pious acts and deeds in fighting against injustice and oppression. Arabic is the lingua jihadica while only parts of the literature, including selected martyr biographies, are specifically translated into other languages. In cases where the martyr is not a native Arabic speaker, his account usually is translated into Arabic and the original language biography is published as well – within the respective lingual networks. The power and the value of jihadist video productions from a lingual outreach perspective in this regard is strategic: any non-native Arabic speaker issues his filmed farewell testimonial, in Arabic referenced as wasiyya, in his native language – Arabic subtitles are added. Only a portion of Arabic native speaker videos, however, are released at a later point with non-Arabic subtitles.

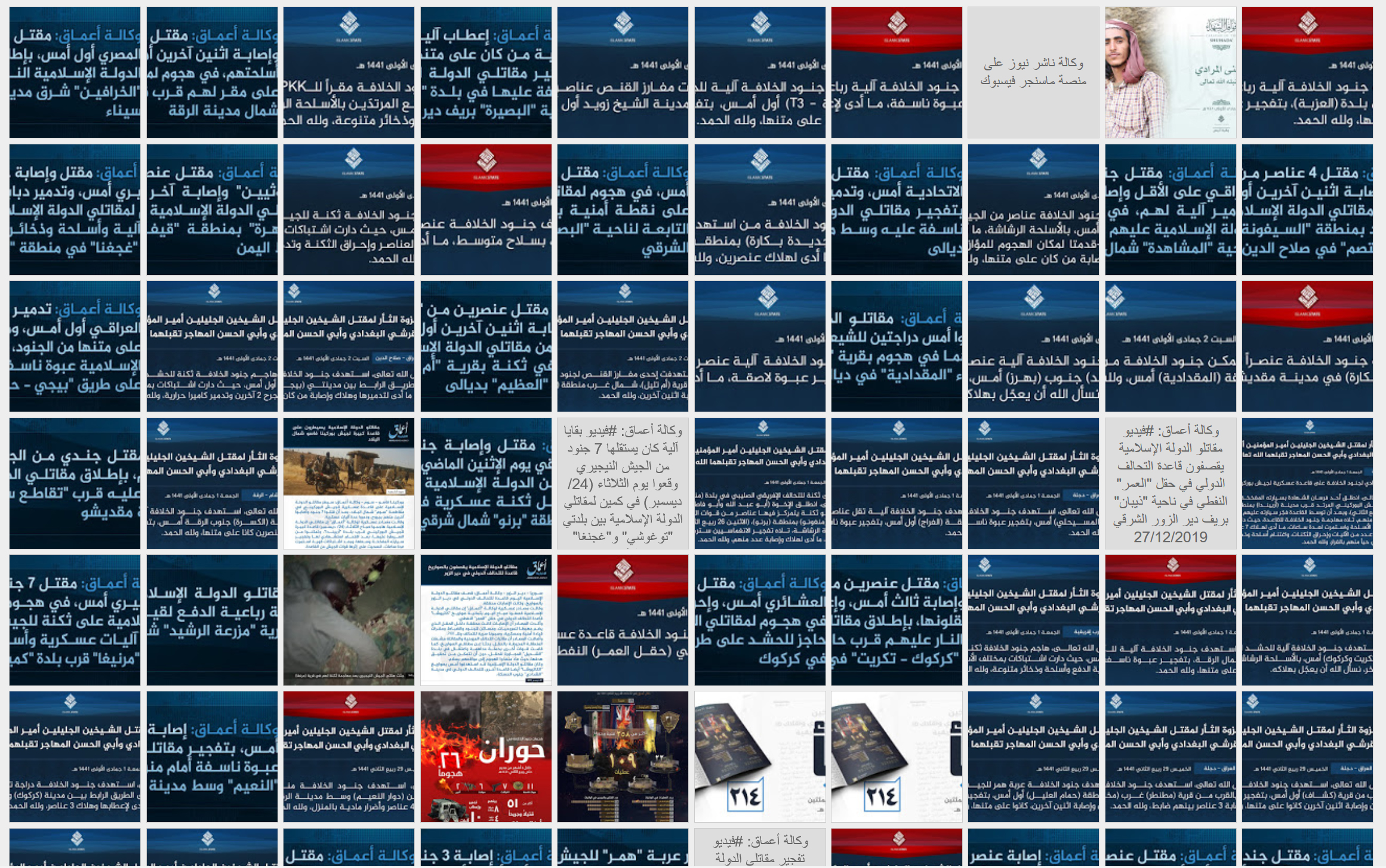

The theology of IS, AQ and any other Sunni extremist groups, however, is based on Arabic-language religious scriptures, not just Qur’an and Sunna, but also references elements of the rich 1,400-year long tradition of Islamic writings. The “Islamic State” applied the theology of AQ in full within its territory – and manages to post videos from other regions of the world as of 2019 where the group manages to control or at times dominate parts of territory.[13] ‘Amaq statements with claims of IS attacks in Congo und Uganda surfaced the past days as well, with pictures showing looted assault rifles and cell phones – and looted tanks and burning village homes in Nigeria. These media items, videos, pictures, writings justifying the occupation of Marawi and the outlook of jihad in South East Asia etc. are ALL in Arabic. In regions where Sunni jihadist groups pop up, Arabic language emerges within the group projected to the outside – core target audience – for native Arabic speakers. Local fighters, as is the case since the existence of VHS tapes featuring local fighters in the 1980s Afghanistan, 1990s Bosnia, Chechnya etc. speak in their local language – with Arabic substitles for the core target audience.

Whereas past AQ generations, in particular in Saudi Arabia[14], had to theologically justify their specific targeting of non-Muslims, IS enforces these theological decrees and legal rulings, in Arabic referred to in the authoritative use of language as fatawa[15] and ahkam: judicial rulings and religious conditions based on chains of arguments allowing or ban i.e. certain behavior or acts.

Jihadist online materials is a rich blend of various media, never short of content, ranging from simple homepages, discussion forums, blogs, various online libraries for texts and videos, to every single social media platform as of writing.[16] The online media footprint today is the development of nearly three decades of committed media work by jihadist actors – with two decades of online cyberpunk styled activism, ensuring that content once uploaded will stay online – and thus findable – somewhere in the rich online ecosystem. This dedicated work has been and is the expression of a strategic discourse on how to conduct jihadist warfare online and has been penned in a highly coherent manner by leading jihadist theoreticians such as Abu Mus’ab al-Suri.[17]

As Reuven Paz, a fluent Arabic speaker (and reader of Arabic language extremist materials) noted in 2007, “Jihadi militancy is … almost entirely directed in Arabic and its content is intimately tied to the socio-political context of the Arab world.”[18] As Ali Fisher notes: “People who live in that socio-political context, or habitus, easily pick up on the factors that make up the ‘narratives’”, and furthermore: “The habitus is itself a generative dynamic structure that adapts and accommodates itself to another dynamic meso level structure composed primarily of other actors, situated practices and durable institutions (fields).” And because habitus allowed Bourdieu, Fisher concludes;

“to analyze the social agent as a physical, embodied actor, subject to developmental, cognitive and emotive constraints and affected by the very real physical and institutional configurations of the field.[19]

In their habitus and manifestation, jihadist media discourses refer to certain principles of belief, or define norms, issue symbols, introduce and enforce wordings, and sources with the intention of having resonance within their target audience. As members of their respective societies, or religiously influenced cultures, they operate from “within” in crafting public messages and framing their narratives, sanctioning violence and defining “justice” and “values” – conveyed by jihadist media groups in a pedagogical fashion, using a highly coded religious language, first and foremost for their target audience: native Arabic speakers, born as Sunni Muslims. It is as if

“the form in which the significant symbols are embodied to reach the public may be spoken, written, pictorial, or musical, and the number of stimulus carriers is indefinite. If the propagandist identifies himself imaginatively with the lives of the subjects in a particular situation, he is able to explore several channels of approach.”[20]

Jihadist media groups operating in Arabic and to a much lesser degree in western languages have perhaps taken note of al-Suri’s “Message to the British and European Peoples and Governments regarding the Explosions in London”, July 2005, where he outlined the Internet as the most important medium to propagate and spread the jihadists demands and frame of reference in general.[21] He referred to “the jihadi elite” residing in Europe to partake in this venture.

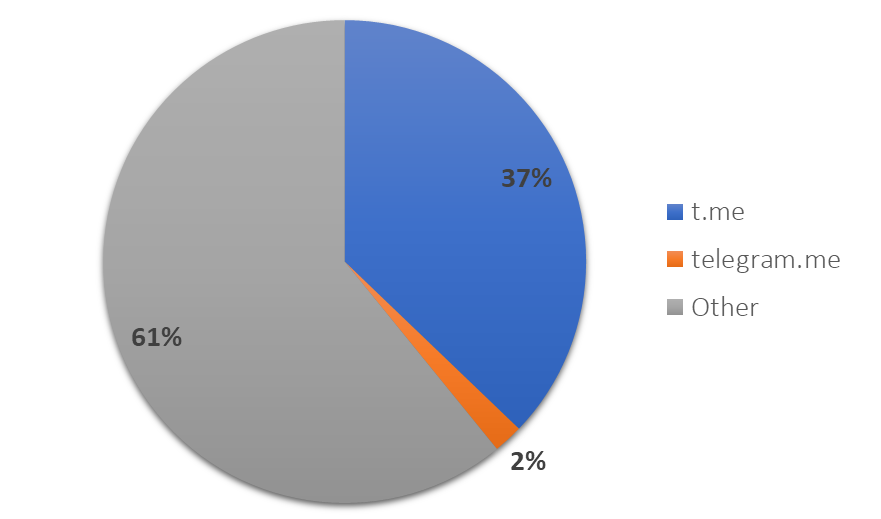

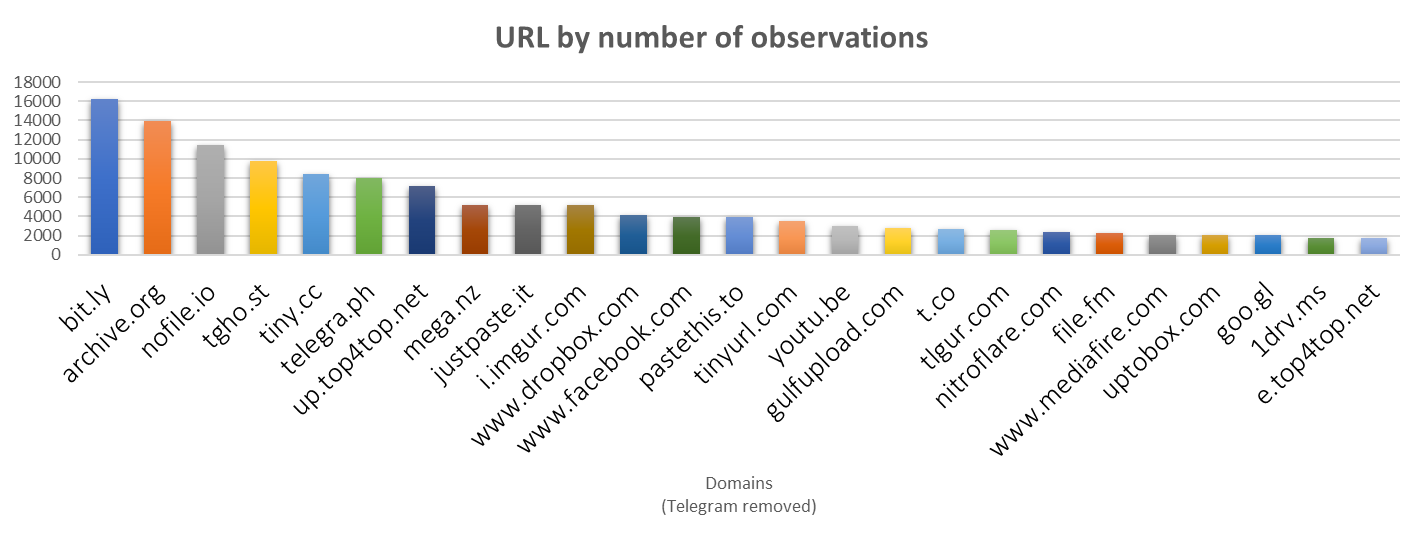

With the rise of the Islamic State and their declaration of the caliphate in mid-2014, the propaganda and the interspersed media strategies to fan-out such content had reached an unprecedented peak. The move by IS to shift to social media (first Twitter 2012 until late 2015, then Telegram 2016 to as of writing (2019)[22], with a change of modus-operandi)[23], their supporters, like other Jihadist groups, have become increasingly adept at integrating operations on the physical battlefield with the online effort to propagate their ideology (=theology) and celebrate their ‘martyrs’, being able to echo contemporary stories to the rich literal corpus that exists since the 1980s.

[1] For example referred by ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam in his 1989 sermon in Seattle, USA, telling the stories of the war against the Soviets and why the ultimate goal can only be to re-establish a Islamic State. ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam,

[2] Yemen / Mali source

[3] ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam, al-jihad bayna Kabul wa-l Bayt al-Maqdis, Seattle, 1988.

For a contextual reading, Nico Prucha, “Abdallah ‘Azzam’s outlook for Jihad in 1988 – “Al-Jihad between Kabul and Jerusalem””, Research Institute for European and American Studies (2010), http://www.rieas.gr/images/nicos2.pdf.

[4] ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam, Muqaddima fi-l hijra wa-l ‘idad, 85.

[5] Reuven Paz, The Impact of the War in Iraq on the Global Jihad, in: Fradkin, Haqqani, Brown (eds.); Current Trends in Islamist Ideology, Vol 1, The Hudson Institute, 2005, 40.

[6] Nico Prucha, “Die Vermittlung arabischer Jihadisten-Ideologie: Zur Rolle deutscher Aktivisten,” In: Guido Steinberg (ed.), Jihadismus und Internet: Eine deutsche Perspektive, Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, October 2012, 45-56, http://www.swp-berlin.org/de/publikationen/swp-studien-de/swp-studien-detail/article/jihadismus_und_internet.html.

[7] Of the many works from this time, the accounts of martyrs by ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam are popular to this day: ‘Abdallah ‘Azzam: ’Ashaq al-hur” martyr biography collection, http://tawhed.ws/dl?i=pwtico4g, accessed August 29, 2013. To give readers an impression, this book by ‘Azzam is

[8] The al-Ansar mailing list, a branch of the al-Ansar online forum, released a collection of martyrs who died in Chechnya: al-Ansar (ed.): qissas shuhada’ al-shishan, 2007; 113 pages.

[9] This tradition was continued in the 1990s with the influx of Arab foreign fighters in Bosnia, see for example the 218 page long collection by: Majid al-Madani / Hamd al-Qatari (2002), Min qissas al-shuhada al-Arab fi l-Busna wa-l Hirsik, www.saaid.net

[10] Abu ‘Ubayda al-Maqdisi and ‘Abdallah bin Khalid al-‘Adam. Shuhada fi zaman al-ghurba. The document was published as a PDF- and WORD format in the main jihadist forums in 2008, although the 350-page strong book was completed in 2005.

[11] With al-Qa’ida on the Arab Peninsula (AQAP) active, a bi-monthly electronic magazine, the Voice of Jihad, was featured and martyr stories had been released online as well. The most prominent martyrs are featured in a special “the Voice of Jihad” electronic book (112 pages): Sayyar a’lam al-shuhada’, al-Qa’idun website, 2006.

[12] Sayyar a’lam al-shuhada‘ was a series that featured the martyr biographies in 2004-2006; the collected martyr biographies (in sum 212 pages) had been re-released by al-Turath media, a media organization that is part of IS in 2018. Since the launch of IS’ weekly newspaper al-Naba’, prominent martyr stories have been featured there.

[13] As displayed in IS videos, i.e. Hijra wa-l qital, Wilayat Gharb Afriqa (January 15, 2019) or Radd al-Wa’id, Wilaya Diyala (January 29, 2019).

[14] Thomas Hegghammer, Jihad in Saudi-Arabia: Violence and Pan-Islamism since 1979, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010.

[15] Plural for fatwa.

[16] For a discussion on how Twitter was used by jihadist actors: Nico Prucha and Ali Fisher. “Tweeting for the Caliphate – Twitter as the New Frontier for Jihadist Propaganda.” CTC Sentinel (Westpoint), June 2013, http://www.ctc.usma.edu/posts/tweeting-for-the-caliphate-twitter-as-the-new-frontier-for-jihadist-propaganda

[17] Lia, Brynjar, Architect of Global Jihad: The Life of Al Qaeda Strategist Abu Mus’ab Al-Suri, New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

[18] Paz, Reuven. “Reading Their Lips: The Credibility of Jihadi Web Sites as ‘Soft Power’ in the War of the Minds.” (2007).

[19] Ali Fisher, How 6th Graders Would See Through Decliner Logic and Coalition Information Operations, Onlinejihad, January 2018, https://onlinejihad.net/2018/01/26/how-6th-graders-would-see-through-decliner-logic-and-coalition-information-operations/

[20] Harold D. Lasswell, The Theory of Political Propaganda, The American Political Science Review, Vol. 21, No. 3. (Aug., 1927), 627-631, http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0003-0554%28192708%2921%3A3%3C627%3ATTOPP%3E2.0.CO%3B2-L.

[21] Abu Mus’ab al-Suri, ila Britaniyyin wa-l Eurupiyyin bi sha’n tafjirat London July 2007 wa-mumarissat al-hukuma al-Britaniyya

[22] Although

[23] Martyn Frampton with Ali Fisher, and Nico Prucha. “The New Netwar: Countering Extremism Online (London: Policy Exchange, 2017).

As of 2019, the Islamic State, but also AQ or the Taliban continue to operate on Telegram and from this protected realm newly produced propaganda is injected into online spaces that are (more) accessible than the closed and hard to find groups on Telegram.