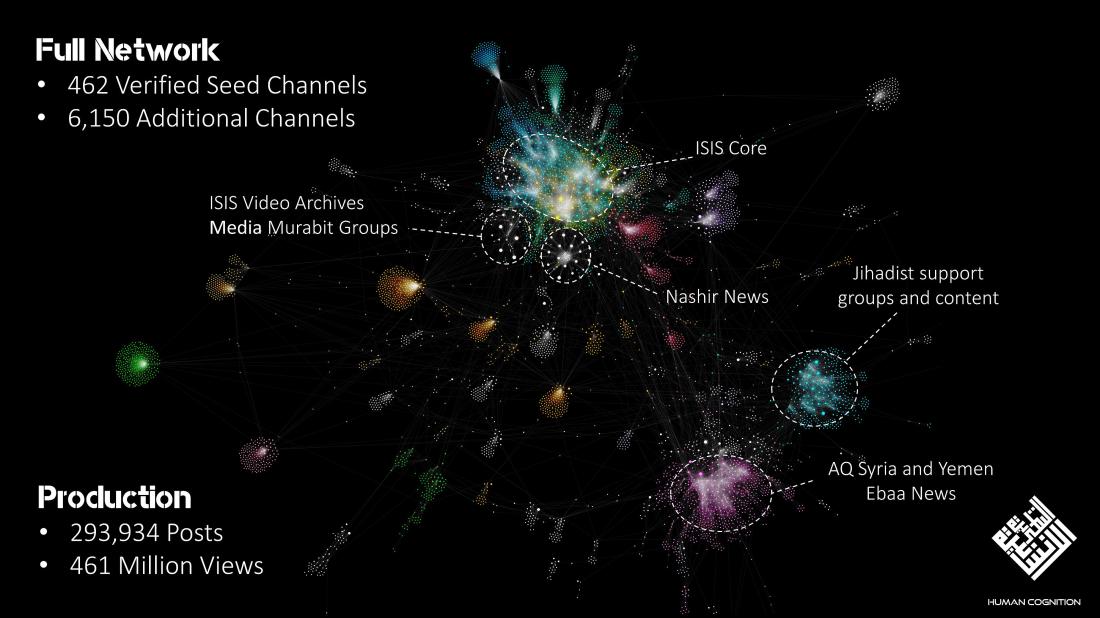

This post looks at a network of 462 human verified Jihadist channels on Telegram and over 6,000 additional Telegram channels and groups on which they draw. It demonstrates that the network is much bigger and exhibits a greater level of interconnection than indicated by recent references to munasir and supposed Core Nashir Channels Telegram. The post then highlights the ‘veil of silence’ that has been cast over the majority of activity conducted by the Jihadist movement on Telegram – activity which is primarily in Arabic, focuses on applied theology, and references a vast library of earlier writing, audio and video.

The use of Telegram by the Jihadist movement has attracted the attention of politicians, who have called on platform owners to deny the movement ‘safe spaces‘ – with inevitable push-back from others including Telegram CEO Pavel Durov. At the same time, rumors circulate of Silicon Valley VCs looking to invest in Telegram, while many column inches have been filled with the usual punditry and superficial commentary about ISIS and social media.

Nashir / News

The often referenced Nashir and other news related channels are a natural starting point for analysing Jihadist groups. Many of this type of channel allows users to see the other followers who are also members of that channel. Network Analysis shows the real number of users in the network (6,266 users) and the clusters of users (blue dots) who make similar combinations of choices about the channels to follow (orange dots).

Channels on the right of the network focus on the formally branded content distributed via Nashir and Amaq channels. Those channels on the left tend to blend the formally branded content with a greater level of supporter generated and affiliated media foundation content. Far from being less important, due to being ‘unofficial’ as is often presented, this blending of content reflects the shared purpose, rather than shared organisational structure, as had been outlined by Abu Mus’ab as-Suri over a decade ago.

The BlackLight image feed (which updates with newly posted content from Jihadist Channels every 90 seconds) frequently shows a wide variety of content which ranges from branded content to pictures of former ideologues and leaders, to imagery which conveys concepts which will resonate with sympathizers versed in Jihadist theology, that of course is distributed primarily in Arabic.

The BlackLight image feed (which updates with newly posted content from Jihadist Channels every 90 seconds) frequently shows a wide variety of content which ranges from branded content to pictures of former ideologues and leaders, to imagery which conveys concepts which will resonate with sympathizers versed in Jihadist theology, that of course is distributed primarily in Arabic.

Wider Telegram Network

This range of content is inline with what we expected to find. Nico Prucha has taken “a closer look at what Telegram is, and how IS uses it for different purposes: not only operationally, but also for identity building“. More than just narrowly defined ISIS branded content, the range of content “conveys a coherent jihadist worldview, based on theological texts written by AQ ideologues and affiliates as far back as the 1980s”.

To break away from the narrow discussion of ISIS content, we analysed the wide ecosystem of Jihadist channels. This ecosystem allows the Jihadist groups to maintain their resilience and distribute the full range of content out of view from those focused on Nashir / News content.

The graph is based on 290,000 posts and shows the content sharing behaviour of 462 human verified Jihadist Telegram channels, and over 6,000 channels from which they share content. Initial observations:

- The graph shows that Jihadist Telegram Channels form a series of interconnected clusters.

- Despite attracting the greatest attention from Western commentators, the Nashir News cluster is a tiny part of the overall ecosystem.

- AQ and ISIS clusters are distantly connected.

- There is a cluster of Jihadist sympathisers and supporters which align closely with neither ISIS nor AQ.

- The creation of content archives on Telegram ensures users who see themselves as murabiteen (horse backed warriors) are able to access the content needed to conduct Ghazwa (raids) onto other platforms.

While the Nashir gain the attention of commentators and pundits, there is a large number of channels and huge amount of content going undetected. This content is also reaching large numbers of people, given that the content in the 293,000 posts has been viewed over 460 million times. (This is the number once the duplicate views have been removed). Below, for example, has been viewed over 309,000 times.

A subordinating silence

Caron E. Gentry and Katherine E. Brown have both shown how particular approaches, including cultural essentialism and neo-Orientalism, can cause a ‘subordinating silence’ which veils particular groups or perspectives from view.(1) These, like many of insights derived from the work on subordinating gendered narratives about terrorists who are female, provide valuable perspectives and parallels closely the issue of which parts of Jihadist ideational content matter to, or get attention from, Western researchers and policymakers.

As Caron E. Gentry has shown, the women who gain media attention are those “that present threats to the Western ‘us’ and not the Middle Eastern ‘other’.” Specifically highlighting coverage of women who either left the west to fight in Iraq, or with ties to AQ and as such threatened to attack Western interests elsewhere. By contrast, for ‘women who did not (yet) pose a threat to Western interests…, virtually no image exists in the public eye. They almost do not exist’.(2) Similarly one finds many studies of English language sources, with significantly fewer studies of the Arabic sources – despite Arabic being the primary and vastly more heavily used language of the Jihadist movement.

As the late Reuvan Paz noted, the movement is “almost entirely directed in Arabic and its content is intimately tied to the socio-political context of the Arab world”.(3) Yet the vast majority of research focuses on English sources. Perhaps this is the content Western researchers are able to find, or because so few researchers are able to listen to and understand the nuances of spoken Arabic nor read Arabic quickly enough to digest the volume of content which circulates in Arabic each week. It is hard to tell definitively which of these two interrelated problems cause the phenomena, but the result is a vast overexposure of sources in English compared to those texts meaningful to the core of the movement – written in Arabic.

Above, the pdf version of issue 117 of al-Naba has been viewed over 7,000 times. Yet analysis of 12-16 pages of Arabic text by al-Naba’ warrants barely a mention, and is erroneously given the same weight as a single picture. Equally, text and images such as those below are often excluded from ‘analysis’ because they come from Amaq, despite being viewed over 9000 times on Telegram alone.

Both items are from the notorious Nashir channel, which is often cited and referred to in the context of IS’ media decline. One may wonder though, why the number of times for instance the al-Naba’ edition has been downloaded in the Telegram application never gets a mention. Perhaps letting slip that this newspaper usually gets around 7000 – 8000 downloads in just the Nashir channel, Amaq posts can get 10,000 views and some Nashir content has been viewed over 300,000 times, contradicts the drum beat that ISIS media is in decline?

Here the study of rhetoric in gender subordination provides a valuable explanation of how such a process can cause a ‘veil of silence’ to descend over an entire area of study.

As Caron E. Gentry wrote:

Across time and place in global politics, rhetoric has often been used to perpetuate certain social ‘truths’ and norms. A speaker or author uses language to direct an audience toward a manufactured truth, one in which some information is emphasized while other information is concealed. In this way, the speaker designates certain ideas, norms, and events superior to others and ignores actions or events that might challenge them.(4)

With a particular focus on neo-Orientalist Narratives, Gentry highlights:

The othering so intrinsic to neo-Orientalism is deeply troubling because it blinds scholars, researchers, and law enforcers to any deeper realities or nuances in people’s lives.(5)

Whether caused by neo-Orientalist perspectives or other reasons, the veiling of particular aspects of the Jihadist movement through ‘terministic screens’ proposed by Kenneth Burke, means ‘the rhetor uses terminology that leads an audience to a specific figurative location (reflection) rather than to an unwanted place (deflection)’.(6)

Focusing only on a few munasir and supposed Core Nashir Channels is particularly dangerous as these are only the channels most readily findable by those in Western and predominantly English language dominated habitus. While much has been made of alleged access to a few secretive ISIS Telegram Channels, the data presented here highlights that approach risks becoming a terministic screen reflecting only a particular part of the Jihadist movement. See, for example, the announcement of a ‘total collapse’ of ISIS media. A month later, the initial fanfare had become ‘Total Collapse … Postponed‘ as the same commentators struggled to explain why ISIS media was on the rise again.

The narrow focus on ISIS branded content analysed from a Western habitus is, as Katherine E. Brown wrote in her discussion of istishhadiyyat (female martyrdom operatives), further compounded by the security frame in which it is set:

in this mainstream view in which the principal frame of reference is the state, and in particular Western states, female suicide terrorism simply becomes a variant of an already known threat to the state. This security approach consequently leads to homogenization based on method of attack and its security impact rather than a recognition of the politics of those involved…. Research that adopts the security approach is thus blinded by the glare of the explosion: the corporality and immediacy of the violence and state responses are overexposed at the expense of other features of the phenomenon.(7)

There are striking parallels between the subordination of gendered narratives and subordination of Arabic sources, by the prioritization of sources accessible to a Western and English speaking audience. In the study of the current movement, scouring ISIS English language magazines for European locations, repeats the overexposure of Western State responses.

Prioritising the impact on Western countries means the underexposure of the Arabic theologically driven core of the movement. Likewise interpreting the theologically driven, primarily Arabic content using Western terms and solely English language publications risks creating a ‘subordinating silence’ around the intentions and strategy of the Jihadist movement. Particularly if commentators are still fast forwarding through videos showing violence and wondering to whom ISIS might be speaking.

Notes:

- Brown, Katherine E. 2011. “Blinded by the Explosion? Security and Resistance in Muslim Women’s Suicide Terrorism,” in Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, eds. Women, Gender, and Terrorism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 194-226.

- Gentry, Caron E. 2011. “The Neo-Orientalist Narratives of Women’s Involvement in al-Qaeda.” In Laura Sjoberg and Caron Gentry, eds. Women, Gender, and Terrorism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 176-193

- Paz, Reuven. “Reading Their Lips: The Credibility of Jihadi Web Sites as ‘Soft Power’ in the War of the Minds.” (2007)

- Gentry, Caron E. 2011. “The Neo-Orientalist Narratives of Women’s Involvement in al-Qaeda.” In Laura Sjoberg and Caron Gentry, eds. Women, Gender, and Terrorism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 176-193

- ibid.

- ibid.

- Brown, Katherine E. 2011. “Blinded by the Explosion? Security and Resistance in Muslim Women’s Suicide Terrorism,” in Laura Sjoberg and Caron E. Gentry, eds. Women, Gender, and Terrorism. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 194-226