Western habitus and Jihadist media:

The understanding of the jihadist movement is a research task which requires collaboration between data analysis and subject matter expertise, a formulation Jeffery Stanton described in his book Introduction to Data Science.

Previous posts have focused on the role of subject matter expertise, and how the study of the Jihadist movement has tried to understand it in terms of street criminals, gangsters, individuals obsessed with computer games (particularly first person shooters), and a desire to go from zero-to-hero. These interpretations originate from the attempt to view the subject matter – Jihadist media – through a Western and predominantly English language lens. In this lens, not even Latinized Arabic key words from the rich blend of Arabic dominated theological motifs are reflected upon sufficiently. This traps the interpretation within specific perceptive dispositions that Pierre Bourdieu calls habitus.[i] These interpretations frequently lack any attempt to address the theological aspects of the movement, even the simple references in the titles of media products go unnoticed. This, as a consequence, leaves the analysis dislocated from the repeated referencing of the concepts, which link together to construct chains that anchor contemporary media to the foundations created by scholars stretching back through the history of Jihadist writing, (and furthermore, the redundant yet coherent use of historical writings used by jihadists to enhance and enrich their posture).

For example, most discussion and interpretation of the series Salil al-Sawarim (SAS), located in a Western habitus, focused on the Hollywood style or slick production values – just as understanding of the movement often revolves around ideas of ‘brand’ and ‘marketing’. However, as noted in the previous post SAS:

is particularly illustrative of this emphasis on theology. Readers sufficiently initiated into the mainly Arabic language corpus of Sunni extremist theology will understand the title’s particular reference right away;[1] it refers to the book al-Sarim al-maslul ‘ala shatim al-rasul, “the Sharp Sword on whoever Insults the Prophet.” Its author is 13th century Islamic scholar Ibn Taymiyya (1263-1328 AD),

Equally consider the sound effect used to underscore references to Ibn Taymiyya’s writings in numerous AQ and IS videos. It is no coincidence that it is a high pitched metallic sound effect which recreates a sword being drawn from its scabbard.

Interpreting the movement with references to a street crime, zero-to-hero, and gangsta lifestyle, creates an impression recruits are being lured to join ISIS with the promise of Big Screen TVs, blunts, 40s and bitches… (to quote ‘Steve Berman’).[ii] These interpretations lack any attempt to address the theological aspects of the movement, nor encoded cultural understandings, and the meaning evident to those from (or sufficiently initiated into) an alternative habitus.

William Rowlandson argues, definitions are “really a debate about who owns the words”.[iii] Framing the interpretation of Jihadist media within a Western habitus focuses interpretation firmly within the comfort zone of English speaking commentators who often have little familiarity with the theological and historical reference points used by the movement, nor a nuanced understanding of the concepts expressed by Jihadists in Arabic. To maintain their ownership over such interpretations, it has become increasingly important for some commentators to downplay the role of theology.

Instead, bolstered by a focus on defecting European Foreign Fighters, these commentators attempt to wrest the analytical locus of the jihadist movement away from the complex, and unfamiliar Arabic core – preferring instead to locate understanding within a Western habitus. This approach fences off alternative world views and further seeks to extend Western hegemonic ownership over meaning – developed since 9/11 became a moment of universal temporal rupture.

Western policymakers reviewing recent media statements, commentary and research will have found a confused range of interpretations for the Resilience and Appeal of “Islamic State” media content. This confusion is as often due to an imbalance between the level of subject matter and data analysis expertise. For example, the data analysis of ISIS networks on VK, deployed a robust data analysis approach for the online phase of the research, but from the outset struggled with the subject matter. The authors appeared surprised to find women prominent in the digital outreach efforts.

However, as Saudi former Usama bin Laden bodyguard and first-generation leader of AQAP Yusuf al-‘Uyayri wrote in ‘The Role of the Women in Fighting the Enemies’:

the woman is an important element in the struggle today, and she must participate in it with all of her capacity and with all of her passion. And her participation does not mean the conclusion of the struggle – no. Rather, her participation is counted as a pillar from amongst the pillars that cause victory and the continuation of the path.[iv]

The document highlights women as fighters and participants in battle (mujahidah being the female form of mujahid):

[T]o show the importance of your role in this clash today between the religions of Kufr and the Religion of Islam, and especially in the new crusade that the world is waging against Islam and the Muslims under the leadership of America, then we must remind you of an aspect of your role, reflected in the image of the Mujahidah of the Islamic Golden Age.

While acknowledging limitations on the involvement in battle – outside of specific circumstances – the document states

… we want you to follow the women of the Salaf (female companions of the prophet) in their incitement (inspire) to fight and their preparation for it and their patience on this path and their longing to participate in it with everything in return for the victory of Islam.

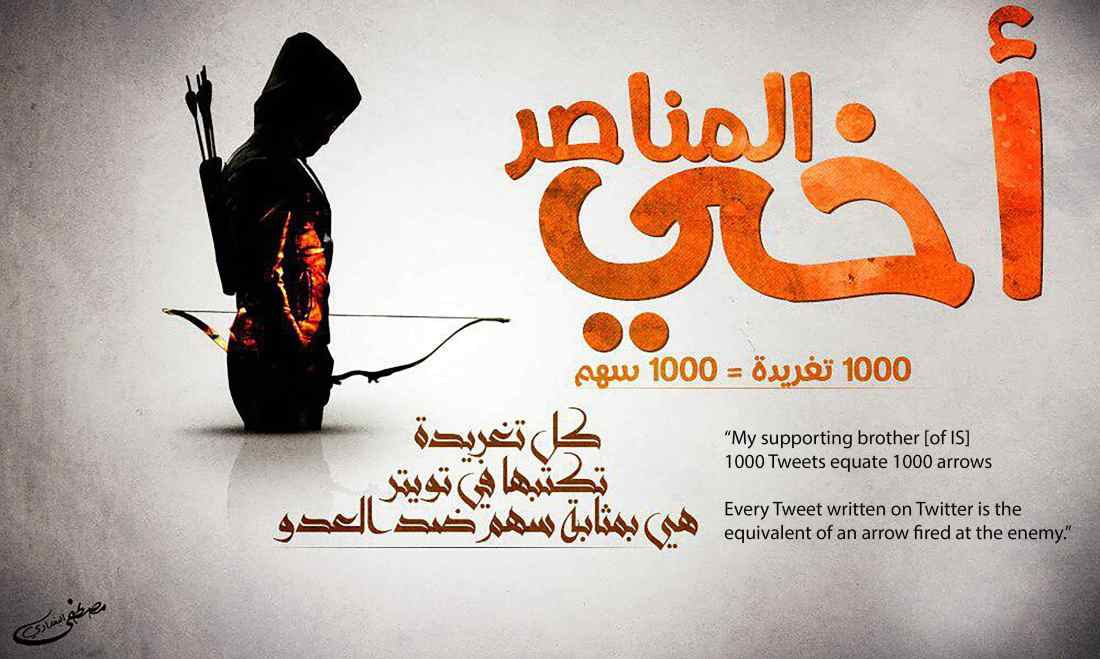

Far from being unlikely to be involved in online activities, this emphasis on incitement, preparation, and participation should highlight the expected role women may play within the online struggle – including on VK.

Familiarity with these texts is not just a niche historical interest. AQAP theologians such as Yusuf al-‘Uyairi and their many writings have long mattered to IS (not just in the time since they caught the attention of commentators as they swept into Syria). Many of the Arabic language productions by IS have strong lingual and theological ties to content produced by the original incarnation of AQAP, yet IS was the first group to have the room, territory and thus resource to apply the otherwise theoretical theology that was brought into organized existence by key leaders and theologians such as al-‘Uyairi. His study circles, strategic writings, sober analysis of U.S. intervention into Iraq etc. are reflected in the structure and output of contemporary IS media releases and notions. Furthermore, a eulogy of al-‘Uyairi (died 2003) by his brother in arms al-‘Awshan (who was also killed shortly after) was downloaded nearly 3,000 times in just one core IS-Telegram channel.

Data Science:

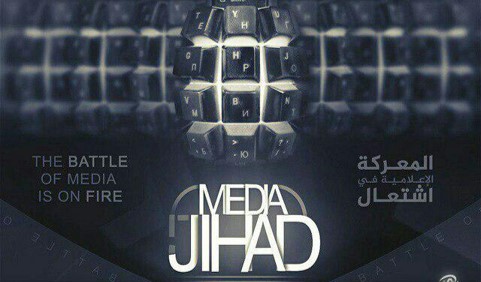

Familiarity with subject matter is one aspect of data science, the other is the familiarity with data handling and statistical techniques. One of the most common elements of commentary (and confusion) is the question of how much ISIS content is being produced, and what it looks like – sadly fewer column inches are allotted to the strategic purpose this content serves.

Since mid-September the stream of commentary, reports, and presentation claiming to show some element of the online presence or Virtual Caliphate has gathered pace. However, as methods vary wildly, and statements are often ad hoc responses what an individual personally saw on Twitter, rather than explanations of research that carries predictive value, politicians can be forgiven their moments of confusion.

Take these statements – both in November from Charlie Winter, one of the proponents of the flawed concept of a Virtual caliphate:

“The caliphate will continue to exist no matter what happens on the ground,”[v]

And

“My latest on the state of #IS’s virtual caliphate. Bottom line up front: It’s not doing too well these days”.[vi]

September:

Back in late September he told a Wired security event about the ‘Virtual Caliphate’:

“There’s a lot of propaganda coming out on a daily basis,” … “Hundreds and hundreds of unique media products, videos, magazines, radio bulletins, in lots of different languages coming out every single day.”[vii]

Tech World reported from the event:

ISIS and its central media office, Winter claims, is “really effective” at keeping up that flow of information – and the propaganda side is something that the group strongly tries to maintain. “I think some of them are addicted to this propaganda, it’s something the group really tries to cultivate, the interdependence between the brand and supporters,” he says.

October:

In October the claim changed, now ISIS had only produced a total of 300 items for the month of September. This claim included a graphic which purported to show “#IS’s media machine is contracting. A large proportion of the propaganda apparatus is now almost totally dormant”.[viii]

It later transpired that to produce the impression that sections of the ISIS media apparatus were “totally dormant” any foundation or province thought to have produced 4 or fewer pieces of content was excluded.

Despite the grainy resolution of the accompanying graphic it was possible to see that the approach had significant methodological problems. The viewer could make out which provinces were considered ‘dormant’. These included al-Furat, Somalia, Khurasan, Bayda’, Anbar, & West Africa. The problem was simple: all these actually produced more than four pieces of content in September.

Publishing the image provided conclusive proof that from a data science perspective, the research is not analysing ISIS production, but recording the declining ability of a particular individual to locate ISIS content.

Furthermore, the impact of the methodological limitations means that from a data science perspective the graphs showing ‘content type’ actually record the type of content which this individual is able to find – not an assessment of the type of content ISIS is actually producing. A subtle difference, but one which makes all the difference in data science.

Equally problematic, this analysis equates the publication of a single photo with that of an hour-long video and a 16-page newspaper. As a result, the organisation that published the 46 minute speech by Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, at the end of September 2017 is recorded as dormant because it only produced the first recording of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi to be released in the last 10 months.

It should be needless to write, this audio-release by al-Furqan is of much greater importance than a single image, or photo report – at least for IS sympathizers and operatives. Although currently we still find ourselves having to write it.

November:

In November, the claims of drastic decline continue; “Nowadays, IS propagandists can barely get out 20 pieces of media in a week”.[ix] As in October, from a data science perspective the claim is based on the declining ability of a specific individual to find content, not actual IS production.

The gulf between rhetoric and reality continues to widen.

November has witness the continued weekly production of the 16-page newspaper al-Naba’ with associated infographics (now 106 issues in total) and numerous photo reports, at least 39 at time of writing (22nd November), collectively containing 215 unique images from 11 different provinces, including al-Furat, Khurasan, al-Khayr, Diyala, and the Khalid ibn al-Walid army. In addition, al-Bayyan has continued to be broadcast, providing a range of radio programmes and daily updates (available to stream, and download in MP3, text and pdf versions in a range of languages).

November also saw the launch of a new 16 page magazine al-Anfal along with videos from provinces including al-Baraka which produced two videos & one each from Damascus, Salah al-Din, al-Janub, and Diyala, bringing the total to six without the inclusion of non-Wilayat video production. This volume of production is a far cry from claims “ISIS is struggling to produce 20 items a week”.

In fact, not only does the current content for November eclipse the ‘struggling 20 a week’ mark, on current pace the images alone will exceed the claim of 300 pieces for September. A situation which echoes the 2016 CTC report on ISIS visual production. That report also claimed significant decline in ISIS production. However, subsequent analysis showed ISIS weekly production actually exceeded the CTC estimate of monthly production. (New Netwar p. 38) This was because CTC, just like these more recent claims of decline, were based on tracking the declining ability of the researchers to find content, not the ability of ISIS to produce it.

Given the ongoing level of production, it is hard to see how a data science approach could produce a credible analysis which shows a shift from; “There’s a lot of propaganda coming out on a daily basis” in late September to; “struggling to produce 20 a week” by early November. But this type of confusion is not unusual; the lack of collaboration between data analysis and subject matter expertise regularly results in research which fails to produce a coherent understanding of the information ecosystem. As is often the case these studies bear little resemblance to the observable reality for those able to access and understand the content produced by the jihadist movement.

For example, a Home Office funded VOX-Pol study concluded ‘the IS Twitter community is now almost non-existent’. Yet at the time of the study 40% of known traffic to ISIS content was coming from Twitter. In addition, a presentation during the recent VOX-Pol conference at ICSR contained research showing there were “90 tweets planning terrorist attacks are tweeted per minute”.[x] That conference also produced the rather cryptic statement that “The deep web should be inhospitable, but not too inhospitable”.[xi]

The need to understand how ISIS networks of influence operate at a strategic level is now evident to almost all – and it requires data science based on the collaboration between data analysts and subject matter experts to achieve it. Understanding the information ecosystem is about more than peering down soda straws at handpicked examples; it is about the way different parts of the ecosystem co-exist and intersect; it is about the way the humans behind the screens interact and fundamentally about the content they share. This includes the documents which outline the strategy and tactics which the Jihadist movement currently intends to use.

The Jihadist movement distributes their strategy in their own words, these words should not be obscured by disciplinary siloes, a failure to collaborate, nor an attempt to force the understanding of the movement into a Western, predominantly English language, habitus.

Notes:

[i] The influence of habitus within Critical Terrorism Studies, particularly with reference to 9/11 as a point of temporal rupture is discussed by Harmonie Toros. While this focuses largely on temporal elements the approach is equally applicable here.:

Harmonie Toros, “9/11 is alive and well” or how critical terrorism studies has sustained the 9/11 narrative, Critical Studies on Terrorism Vol. 10 , Iss. 2, 2017

[ii] Track 6, The Marshall Mathers LP

This deliberately crass reference to Dr Dre is used to emphasise the gulf between the imagery of western gangsta rap and what Jihadist media actually contains.

[iii] Rowlandson, W. 2015. Imaginal Landscapes: Reflections on the Mystical Visions of Jorge Luis Borges and Emanuel Swedenborg. London: Swedenborg Society.

Quoted in Harmonie Toros, “9/11 is alive and well” or how critical terrorism studies has sustained the 9/11 narrative, Critical Studies on Terrorism Vol. 10 , Iss. 2, 2017

[iv] Yusuf Bin Salih Al-‘Uyayri, The Role Of The Women In Fighting The Enemies, (Translated version) At-Tibyan Publications

[v] https://www.thedailybeast.com/winning-the-battle-losing-the-message-inside-americas-utter-failure-to-counter-isis-propaganda

[vi] https://twitter.com/charliewinter/status/928586607271268352

[vii] https://www.techworld.com/security/how-isis-runs-its-central-media-operation-3664672/

[viii] https://twitter.com/charliewinter/status/920651518172332032

[ix] http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-41845285